with voice

commands, please use

the Chrome browser on PC

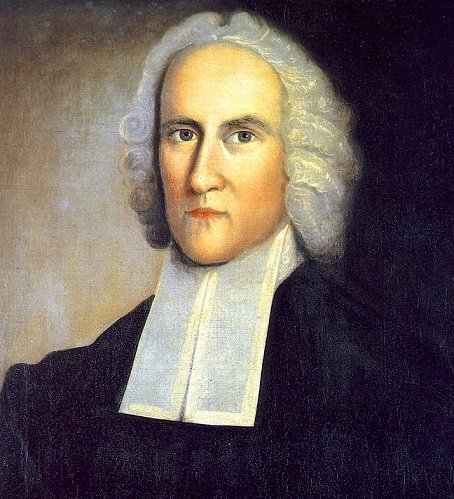

Jonathan Edwards

Date of Birth : October 5, 1703.

Fell As Sleep in The Lord : March 22, 1758.

Marriage : July 20, 1727.

Children : 11The sense I had of divine things, would often of a sudden kindle up, as it were, a sweet burning in my heart, an ardor of soul, that I know not how to express.

Jonathan Edwards was born in East Windsor, Connecticut, to Puritan parents Timothy and Esther Stoddard Edwards. Of their eleven children, he was the only son.

Jonathan Edwards was born in East Windsor, Connecticut, to Puritan parents Timothy and Esther Stoddard Edwards. Of their eleven children, he was the only son.

Times in northern New England were turbulent and there was constant friction between the settlers and the French and Indians of Canada. For example, less than a year after Jonathan’s birth on February 29, 1704, the town of Deerfield was attacked by roughly two hundred braves and a small contingent of Frenchmen. Fifty-six of its roughly three hundred residents were killed, and another one hundred were kidnapped. Jonathan’s uncle, John Williams, was taken with his family in the attack, though he later escaped with some of his children. His wife and two youngest children were killed.

The Puritan mindset interpreted such calamities as signs of the times for God’s new covenant people, which they believed themselves to be. Like the nation of Israel, Puritans believed they were blessed or punished according to their obedience or disobedience to God. For them, the Deerfield Massacre and kidnappings were likened to Israel being carried off into Babylon, while their return was likened to Nehemiah’s rebuilding of Jerusalem. With death and hardship always near, the Puritans felt they had to hold God even closer if they were to keep any hope of survival. Edwards grew up with the constant burden of praying for the protection of family members several times a day.

A Young Scholar

Edwards sensed God’s calling on his life rather early. He recorded in his journals that he spoke often about God to the other boys his age, and together they built a place to pray in the woods. He wrote that for a period of months, he and the other boys would go there as often as five times a day to seek God.

At the age of thirteen, Jonathan enrolled at the Collegiate School of Connecticut, which would later become Yale University. While studying for the ministry, Edwards devoured books in the largest library in the area, reading works not only particular to ministry, but also from various other fields. He graduated in 1720 at the head of his class but stayed for two more years to pursue a master’s degree.

At age sixteen while still at college, Jonathan had a near-death experience. He became very ill with pleurisy 1 and was terrified that he would die without being prepared for eternity. He described the experience as being “shook over the pit of hell” - imagery that would reappear years later in his most famous sermon. Though he recorded that during this time he committed himself to God in a new way, when he eventually recovered from his illness, he “fell again into his old ways of sin” and continued to have “great and violent [spiritual] struggles.” 2

This hot and cold relationship with God went on throughout Jonathan’s formative years. His father held to a strict Calvinistic doctrine that individuals would know whether or not they were saved through a process of conviction, repentance, and revelation of Christ’s saving grace. His maternal grandfather once told him that, ten to one, those converted would surely know that their experience was real. Since Jonathan struggled with uncertainty, he must have wondered whether God had indeed granted him salvation.

Finally, in 1721, in a regular time of study, the truth of a passage surpassed his rational mind to the point of a revelation: “Now unto the King eternal, immortal, invisible, the only wise God, be honour and glory for ever and ever. Amen” (1 Timothy 1:17). Of this experience, Jonathan wrote,

There came into my soul, and was as if it were diffused through it, a sense of the glory of the divine being; a new sense, quite different from anything I ever experienced before. . . . I thought with myself, how excellent a Being that was; and how happy I should be, if I might enjoy that God, and be wrapped up to God in heaven, and be as if it were swallowed up in him. 3

From this moment on, Edwards determined to understand God and His Word from all aspects, believing that “the more you have of a rational knowledge of divine things, the more opportunity will there be, when the Spirit shall be breathed into your heart, to see the excellency of these things, and to taste the sweetness of them.” 4

A Pastorate and a Young Bride

After graduating from Yale, Edwards accepted his first call to be a pastor in New York. Though he loved the congregation, the church struggled financially and could not pay him an adequate wage, so Jonathan moved back home to Connecticut. His father convinced him to take a pastorate at Bolton, but he left this in a few months to take a teaching position at Yale. Some thought his reason for taking the job at Yale had to do with the daughter of the pastor there, Sarah Pierrepont, who Jonathan described in his journals as sweet and “beloved of that Great Being.” 5 Unfortunately, Jonathan was not yet cut out to manage young men who had grown wild with their first taste of independence, so when his grandfather, the Reverend Solomon Stoddard, invited him to become his assistant pastor at the Congregational Church in Northampton, Massachusetts, he jumped at the opportunity. This was the largest church in New England outside of Boston, and Stoddard, a highly influential man now in his eighties, needed help.

With his new position and steady salary - adequate to purchase land and a home - Edwards now formally pursued courtship with Sarah. They were married on July 20, 1727; Jonathan was twenty-four and Sarah was seventeen. Sarah wore a bright green, satin brocade dress - an exuberant expression of the Puritan celebration of love and marriage. 6

Eleven children were born to Edwards and Sarah: Sarah, Jerusha, Esther, Mary, Lucy, Timothy, Susannah, Eunice, Jonathan, Elizabeth, and Pierrepont. All eleven lived into adulthood, which was extremely unusual for that day and age.

“The Religious Psychologist”

For Jonathan Edwards, there was no division between science and religion. For example, he had a deep interest in spiders, so he carefully studied and categorized them, describing them in great detail as he did so. Jonathan’s remarkable account of a spider weaving a web is still widely read today.

When he would go for a ride in the woods, he always carried a pen, ink, and bits of paper along with straight pins. He used these rides to think and to talk with God, and then he recorded the ideas that came to him and pinned them, in order, to his coat. His wife, vigilant to keep them in order when he arrived home, then carefully unpinned this checkerboard of thought.

Edwards once carefully disassembled a Bible and sewed a sheet of blank paper between each page to allow him to record his notes. He resolved, “to study the Scriptures so steadily, constantly and frequently, as that I may find, and plainly perceive myself to grow in the knowledge of the same.” 7

Edwards was determined to take time to think about the implications of what he observed, going so far as to skip dinner if it threatened to interrupt the flow of his deliberations. As he had done with everything else in his life, he carefully observed and analyzed which foods best suited his mental labour. Some said that his discipline in eating left him thin and frequently ill, but Edwards evidently gave great consideration to his diet, though there is at least one hint of a small indulgence. Jonathan loved chocolate, and A letter remains of his request that a courier to Boston be sure to procure some for him. 8

The Dawn of the Great Awakening

The year after Jonathan became assistant pastor at his grandfather’s church, all of New England experienced the Great Earthquake of 1727. According to some accounts, it began with a flash of light followed by rumbling and shaking that lasted throughout the night. People who were awakened from their sleep crowded together in the streets believing that judgment day had come. The next morning, churches across New England were filled with penitents. Fasts were called for throughout the land several times in the weeks following. It was Jonathan’s first experience of anything close to a revival, though as nerves settled, so did the community’s devotion.

The year after Jonathan became assistant pastor at his grandfather’s church, all of New England experienced the Great Earthquake of 1727. According to some accounts, it began with a flash of light followed by rumbling and shaking that lasted throughout the night. People who were awakened from their sleep crowded together in the streets believing that judgment day had come. The next morning, churches across New England were filled with penitents. Fasts were called for throughout the land several times in the weeks following. It was Jonathan’s first experience of anything close to a revival, though as nerves settled, so did the community’s devotion.

Then Solomon Stoddard died in February 1729 and the church decided to make Jonathan the senior pastor. It was a position he took very seriously. He wrote about climbing the steps to the podium to preach as becoming “the trumpet of God.” 9 Some said he turned into an entirely different person when preaching.

After the sudden death of a young man in April 1734, Jonathan preached a funeral message that encouraged those present to turn away from their sinful lifestyles and focus instead on their eternal rewards. He asked if one was to die so young, what would he have to show for his life? “Consider,” he advised. “If you should die in youth how shocking would the thought of your having spent your youth in such a manner be to them that see it.” 10 Another death, along with another funeral message, continued the renewal of spiritual interest. Reports of changed lives began to pour in. Evenings of “frolicking” were traded for prayer meetings, and soon the great majority of the community - young and old alike - attended such meetings.

By April 1735, the evidence of a changed spiritual atmosphere in the community was undeniable. Edwards himself described it this way:

A great and earnest concern about the great Things of Religion, and the eternal World, became universal in all parts of the Town, and among Persons of all Ages. . . . All other Talk but about spiritual and eternal things, was soon thrown by. . . . The Minds of People were wonderfully taken off from the World; it was treated amongst us as a Thing of very little Consequence. . . . The Temptation now seemed to lie on that hand, to neglect worldly affairs too much, and to spend too much time in the immediate Exercise of Religion. 11

Without being prompted, neighbours took up a collection for the owner of a general store after it burned to the ground. Backbiting and gossiping stopped. Taverns were reported to have emptied. Illness nearly disappeared from the town. Even church services were transformed. Some reports say that more than five hundred people - half of the men - joined the church as a result of the revival.

However, by March 1737, the spiritual condition of Edwards’s congregation was again cold. He described the people as having “eagerness after the possessions of this life” 12 and noted that there had been a return of the heated “party spirit.” He began to pray again for a revival.

True Awakening Takes Hold

By 1739, George Whitefield was already preaching to crowds of thousands in the streets and fields of England and was now coming to the colonies. Edwards wrote to him in February 1740 and persuaded him to come to Northampton, warning him that his people might be more hardened of the heart than others to whom he had preached. A major publicity campaign helped draw the crowds in the cities to hear Whitefield, and when he moved on to Northampton on October 17, 1740, the attention of the masses followed him.

When Whitefield reminded Edwards’s congregation of their closeness to Christ after the last move of God in the area, many began to weep, including Edwards himself, as he saw five years of prayer for revival begin to be answered. Some of his own children came to Christ through Whitefield’s ministering. As Whitefield ministered, it was not uncommon for people to fall out under the power of the Holy Spirit - which Edwards called “faintings.”

There were some instances of persons lying in a sort of trance, remaining perhaps for twenty-four hours motionless, and with their senses locked up; but in the meantime under strong imaginations, as though they went to heaven and had their visions of glorious and delightful objects. 13

The revival continued, and Edwards and Whitefield stayed in contact by letter. Edwards reported the results of the awakening in his area to be greater than the previous awakening of Northampton in 1734.

“Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”

On Wednesday, July 8, 1741, Jonathan was among a team of preachers at Enfield (near the border of Massachusetts and Connecticut) to minister to large numbers of people who were inquiring about how to be saved. Several ministers had been preaching at the ongoing services between Enfield and Suffield. On that Wednesday morning, it was decided at the last minute that they would rest and let Jonathan preach. Jonathan searched his saddlebags and found a sermon he had used shortly before with his congregation. It had little moved them, but he decided to use it again anyway. The passage for the sermon was Deuteronomy 32:35, “Their foot shall slide in due time.” Here is a brief excerpt of the words he spoke that day:

The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect, over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his wrath towards you burns like a fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in his sight; you are ten thousand times so abominable in his eyes as the most hateful venomous serpent is in ours. . . .

And now you have an extraordinary opportunity, a day wherein Christ has flung the door of mercy wide open, and stands in the door calling and crying with a loud voice to poor sinners; . . . many that were recently in the same miserable condition that you are in, are now in a happy state, with their hearts filled with love to him that has loved them and washed them from their sins in his own blood, and rejoicing in hope of the glory of God. How awful is it to be left behind on such a day! 14

Before Edwards could even finish his message, the people became agitated and began crying out. He asked the congregation to be quiet as there was no way to be heard. He never finished the sermon, however, and in the coming months, the community was utterly transformed.

“Trust in God”

Despite this blessed time, Jonathan would never see such revival again, though he would meet individuals such as the young missionary, David Brainerd, whose devotion was unquestionable and moving. In 1750, Jonathan lost his position of twenty-three years at the church in Northampton when he took a hard stand against servicing communion to non-church members, a practice his grandfather had allowed. From Northbridge he went to Stockbridge to become a missionary to the Native Americans. His six years as a missionary turned out to be a gift from God, allowing him to do his best theological writing - work that is still revered today.

Then in September 1757, Jonathan received the news that his son-in-law, Aaron Burr, Sr. had died of malaria - and with it came an invitation for Jonathan to take his place as president of the College of New Jersey, now called Princeton University. Though at first, he resisted, stating he was not educated well enough for the post, after much thought, he agreed to seek counsel from some trusted friends. When they expressed their belief that it was his duty and responsibility to accept the appointment, Edwards broke down in tears before them. He would leave immediately to answer what they believed to be the call of God on his life.

Jonathan travelled with his daughter Lucy and arrived in New Jersey in January 1758. To his surprise, he enjoyed preaching to the students and faculty and was comforted by their warm reception. What’s more, he actually had more time for study and writing than he had anticipated. Settling in Princeton looked promising.

However, at this time, smallpox had spread throughout New England and many were dying. Being the scientific progressive that he was, he had decided years earlier that he would receive inoculation if he needed to. He received the shot on February 13, 1758.

At first, Edwards showed only some slight symptoms of the disease. But weeks later, a severe fever set in, and on March 22, 1758, at the age of fifty-five, Edwards died. Days before he died, knowing that eternity was near, he asked his daughter Lucy to record his last words. As expected, he gave his love to his dear wife and children, calling his relationship with Sarah “an uncommon union.” He requested that his funeral be simple and that any designated funeral money would instead be used for the poor. When those standing around his deathbed thought he was no longer capable of hearing or speaking, Edwards surprised them with these final words: “Trust in God, and ye need not fear.”

Works Consulted

- A respiratory disease of the lungs.

- George M. Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 36.

- Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life, 41.

- Jonathan Edwards, “The Importance and Advantage of a Thorough Knowledge of Divine Truth” (sermon), Christian Classics Ethereal Library, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/edwards/sermons.divineTruth.html (accessed October 17, 2007).

- John Nichols, American Literature: An Historical Sketch, 1620–1888 (Edinburgh, Adam and Charles Black, 1882), 54.

- Elisabeth S. Dodds, Marriage to a Difficult Man: The “Uncommon Union” of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1971), 24.

- Jonathan Edwards, “The Resolutions of Jonathan Edwards,” Bible Bulletin Board, http://www.biblebb.com/files/edwards/resolutions.htm.

- Steven Gertz and Chris Armstrong, “Did You Know?: Interesting and unusual facts about Jonathan Edwards,” Christian History 22, no. 1 [Issue 77] (2003), http://www.ctlibrary.com/6341 (accessed October 12, 2007).

- Helen Westra, The Minister’s Task and Calling in the Sermons of Jonathan Edwards (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 1986), 7, in Marsden, Jonathan Edwards - A Life, 132.

- Jonathan Edwards, Sermon (April 1734), quoted in Marsden, Jonathan Edwards - A Life, 154.

- Jonathan Edwards, The Christian History (1743), quoted in Mintz, S. (2007). Retrieved October 19, 2007 from http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/documents_p2.cfm?doc=230. Digital History.

- Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life, 184.

- Jonathan Edwards, “Revival of Religion in Northampton in 1740–1741,” Jonathan Edwards on Revival (Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 1984), 154, quoted in Hyatt, 2000 Years of Charismatic History, 116.

- Marsden, Jonathan Edwards: A Life,223.

Receive a periodical newsletter about this Author. Links in connection with Articles related to this Author will be periodically sent to your email.

Related Topics : Generals Of God, Roberts Liardon, Jonathan Edwards,

At IUSEFAITH.com and JUTILISELAFOI.COM, we are dedicated to curating and delivering powerful devotionals from genuine, Spirit-led men and women of God. Through reading, analysis, translation, programming, and occasionally content generation, we ensure you receive rich, faith-building resources.

To continue expanding this work and reaching more souls, we are upgrading to a higher hosting plan. If you are led to support this Kingdom mission, kindly reach out via +233 552 524 195 to learn how you can contribute.

Together, let’s advance the Gospel through technology.