with voice

commands, please use

the Chrome browser on PC

Love everybody and fear no man.

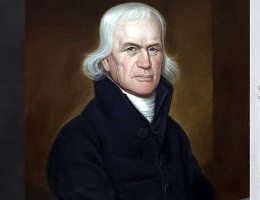

Date of Birth : September 1, 1785.

Fell As Sleep in The Lord : September 25, 1872.

Marriage : August 18, 1808.

Children : 9

It is said sometimes that hard times call for hard men, and this can certainly be said of Peter Cartwright. Peter’s dedication as a circuit rider on the American frontier not only helped establish Methodism as the way of revival in his time but also saw roughly 10,000 converted. That is saying a good deal for a man who spent most of his time preaching to rural communities and small crowds. In his sixty-seven years as a minister, he preached almost 15,000 sermons. His title of “The Backwoods Preacher” was well earned, and he was an American hero to rival the likes of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett. With God’s help, he won the West as no one else ever would.

It is said sometimes that hard times call for hard men, and this can certainly be said of Peter Cartwright. Peter’s dedication as a circuit rider on the American frontier not only helped establish Methodism as the way of revival in his time but also saw roughly 10,000 converted. That is saying a good deal for a man who spent most of his time preaching to rural communities and small crowds. In his sixty-seven years as a minister, he preached almost 15,000 sermons. His title of “The Backwoods Preacher” was well earned, and he was an American hero to rival the likes of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett. With God’s help, he won the West as no one else ever would.

Peter Cartwright was born to Peter Cartwright, Sr. and Christiana Garvin on September 1, 1785, in Amherst County, Virginia, a year and a half before they were married. According to a newspaper story from Civil War times, he was born while his mother was hiding from an Indian attack in a cluster of closely growing cane trees. 1 His father was a veteran of the Revolutionary War. When Peter was about five, the family moved into the newly opened Kentucky territory.

When the family moved west in 1790-1791, Kentucky was still an unbroken wilderness - the land of “canes and turkeys” - with no roads and few towns. It was a Promised Land to many poor Easterners, complete with warring tribes to overcome. Indian fighting was so active that as the group of two hundred families headed west they required an escort of one hundred. Still, not all of the party made it safely through the more settled areas of Kentucky.

“A Wild, Wicked Boy”

The Cartwright homestead was about nine miles south of the county seat, Russellville, just a mile north of the Kentucky/Tennessee border. Though his mother had become a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church, Peter grew up more rogue than Christian with a passion for card playing, horseracing, and dancing. Though his father held some sway over him, his mother wept and prayed constantly hoping for his reform. At times he would be moved by her words, or attend a meeting and vow to seek God more earnestly, but these moments of remorse always came to nothing as he soon found himself again in the company of other young people gambling and dancing.

To make matters worse, his father bought him a fine horse that proved a strong racer and his own pack of cards. While he didn’t cheat, he did become rather proficient at winning money gambling and it became an addiction for him. Peter called himself “naturally a wild, wicked boy.” 2

The Holy Spirit Falls on Kentucky

When Peter was sixteen, revival hit Kentucky through the four-day Communions held by James McGready and others. In his Autobiography, Peter describes his conversion in this way:

In 1801, when I was in my sixteenth year, my father, my eldest half brother, and I attended a wedding about five miles from home, where there was a great deal of drinking and dancing, which was very common in marriages those days. I drank little or nothing; my delight was in dancing. After a late hour in the night, we mounted our horses and started for home. I was riding my racehorse.

A few minutes after we had put up the horses, and were sitting by the fire, I began to reflect on the manner in which I had spent the day and evening. I felt guilty and condemned. I rose and walked the floor. My mother was in bed. It seemed to me, all of a sudden, my blood rushed to my head, my heart palpitated, in a few minutes I turned blind; an awful impression rested on my mind that death had come and I was unprepared to die. I fell on my knees and began to ask God to have mercy on me. . . .

The next morning I rose, feeling wretched beyond expression. I tried to read in the Testament, and retired many times to secret prayer through the day, but found no relief. I gave up my racehorse to my father and requested him to sell him. I went and brought my pack of cards, and gave them to mother, who threw them into the fire, and they were consumed. I fasted, watched, and prayed, and engaged in regular reading of the Testament. I was so distressed and miserable, that I was incapable of any regular business. . . .

In the spring of this year, Mr M’Grady [McGready], a minister of the Presbyterian Church, who had a congregation and meeting-house, as we then called them, about three miles north of my father’s house, appointed a sacramental meeting in this congregation. . . .

To this meeting, I repaired, a guilty, wretched sinner. On the Saturday evening of said meeting, I went, with weeping multitudes, and bowed before the stand, and earnestly prayed for mercy. In the midst of a solemn struggle of the soul, an impression was made on my mind, as though a voice said to me, “Thy sins are all forgiven thee.” Divine light flashed all around me, unspeakable joy sprung up in my soul. I rose to my feet, opened my eyes, and it really seemed as if I was in heaven; the trees, the leaves on them, and everything seemed, and I really thought were, praising God. 3

The meeting lasted without a breakthrough the entire night and more than eighty people found peace with God. This meeting was at the Red River Meetinghouse in June near the beginning of the biggest Communion season ever.

Called to Preach

At the beginning of the Communion season the next year, Peter was surprised when his pastor presented him with a letter acknowledging him as an exhorter for the Methodists.

By the time Peter was eighteen he was a regular circuit rider and was asked to travel with another minister to aid him in the work. Peter’s father objected, but his mother prevailed in urging him to go. Along the route, Peter was asked to give the evening service, which he had never done before and wondered if he was called to do it. He prayed fervently that God helps him, and asked God to give him one convert that night as evidence that he was truly called to preach. That night his preaching was met with tears and sighs, and one young man who was known as a heathen gave his heart to the Lord and joined the church.

He went on to travel the circuit for three months, saw twenty-five more converted, and received six dollars as pay at the end. Peter became known as “The boy preacher” or “the Kentucky boy” and felt his call had been assured.

A Funeral Service Leads to Revival

Peter soon received a request to perform a funeral service in an old Baptist meetinghouse, and when he did, the Holy Spirit fell as He had during the camp meetings. He stayed to minister night and day for a while and at every meeting the Holy Spirit manifested. Peter saw twenty-three saved, but had to contend with the local Baptists for their memberships. Later in his life, he said of the Baptists, “Indeed, they made so much ado about baptism by immersion, that the uninformed would suppose that heaven was an island, and there was no way to get there but by diving or swimming.” 4

Peter continued itinerating and was ordained as a deacon in the Methodist Episcopal Church at the Western Conference in 1806 by Francis Asbury himself. After his ordination, Peter was sent northeast to the Ohio border, and for the first time met Yankees. At first, he had not wanted to go, but when Francis Asbury took him in his arms and said, “O no, my son; go in the name of the Lord. It will make a man of you,” 5 he could hardly refuse. This particular area was filled with various sects such as Universalism, Unitarianism, Deism, etc. and proved a veritable seminary for young Peter as he had to pour through his Bible to find rebuttals to their teachings. During this time, Peter honed his skill and wit as a powerful debater.

Peter Marries

The Conference was in Chillicothe, Ohio on September 14, 1807, roughly two weeks after Peter’s twenty-second birthday. He was assigned a circuit in the Cumberland district, closer to home, under James Ward who was the presiding elder there. In this area, he met and began courting Frances Gaines. As a result, Cartwright broke with the tradition of celibacy set forth by Bishop Asbury and Peter’s Bishop, William McKendree, and married Frances on her nineteenth birthday, August 18, 1808. Of this, he said, “After mature deliberation and prayer . . . I thought it was my duty to marry,” 6 and that seemed enough justification of the act to him, as he had consulted none of his superiors on the matter. They celebrated their infare (a combined wedding reception and housewarming 7 ) with his parents the following September on Peter’s twenty-third birthday.

That year the Western Conference was in Liberty Hill, Tennessee (just south of Nashville) on October 1. Peter left his wife with his family and headed there with the added weight that he would have to tell Bishop McKendree of his marriage. McKendree said he was not sorry Peter had married, but now he would have to settle in one place - something that could significantly hurt his promotion. Peter accepted his grace, but then fired up to show his determination. “It raised my ambitions and I became pretty spunky, and I just said, Now, here goes; I can work for my living, I can split rails, plough, grub, mow, cradle, or reap. I was raised to it.” 8 And he would not give up itinerating. He would work his farm and ride his circuit without compromise. McKendree must have appreciated his determination, for he made him an elder in the Methodist Church before the end of the conference.

Issues of Slavery

As an elder, Peter was expected to get more involved in the politics of the church, and he soon found himself embroiled with the debate about slavery. While the Methodist Disciplines forbid the purchase, sale, or ownership of slaves, southern Methodists in the United States had long disregarded that tenet. Now it was becoming an issue in the west where slavery was allowed but was quickly growing unpopular in the wake of the revivals and the growing support of abolition that they had inspired. It was an issue that Peter had at first avoided, feeling it more political than spiritual. He did, however, feel owning slaves was immoral - but his office as an elder would not long permit any neutrality on the issue of slavery. Members of the Methodist conferences soon became divided along pro-slavery and abolitionist lines. This repeatedly came up when new ministers were nominated for ordination who were slave-owners - could a man who owned slaves be welcomed as a minister for the Methodist Episcopal Church? In his Autobiography, published in 1856, Peter had this to say about the matter:

Slavery had long been agitated in the Methodist Episcopal Church, and our preachers, although they did not feel it to be their duty to meddle with it politically, yet, as Christians and Christian ministers, be it spoken to their eternal credit, they believed it to be their duty to bear their testimony against slavery as a moral evil, and this is the reason why the General Conference, from time to time, passed rules and regulations to govern preachers and members of the Church in regard to this great evil. The great object of the General Conference was to keep the ministry clear of it, and there can be no doubt that the course pursued by early Methodist preachers was the cause of the emancipation of thousands of this degraded race of human beings; and it is clear to my mind if Methodist preachers had kept clear of slavery themselves, and gone on bearing honest testimony against it, that thousands upon thousands more would have been emancipated who are now groaning under oppression almost too intolerable to be borne. Slavery is certainly a domestic, political, and moral evil. 9

Unfortunately, not all of his fellow elders felt this way, as many of them owned slaves themselves, and while Peter’s cantankerous nature won him much support in the cause to end slavery, it also made him a focal point for the opposition which said he was merely doing it to cause trouble and advance his position in the leadership of the church.

A Time for Change and Meddling in Politics

Peter remained in Kentucky until 1824 where he and his wife had had seven children. As their oldest, Eliza, now fourteen, was approaching marrying age on the frontier, Peter became concerned his girls might marry into a slave-owning family and disgrace his standing against the issue, so he sold his land, and early in October of 1824, moved his family to Illinois.

By thirty-nine, Peter had become a formidable man to deal with, whether it was from behind the pulpit, in a personal confrontation, or as a public figure. Though he had left slavers behind, he had now embraced emancipation on a larger scale. In addition to his circuit duties as a presiding elder and his responsibilities in running his farm, Peter ran for a two-year seat in the General Assembly of the Illinois Legislature, coming in fourth out of eleven for three seats in 1826, winning a seat in 1828, losing again in 1830, and winning again in 1832, this time against the formidable opponent, Abraham Lincoln. He would run again in 1834, but withdraw before the election, and thus Lincoln won his first public office. In 1835, he ran for state Senate but lost to Job Fletcher.

Cartwright and Lincoln would again face each other for a U.S. Senate seat in 1846. As one story of this election goes:

During the campaign, Lincoln went to a revival meeting where Cartwright was to preach. In the course of the meeting, Cartwright announced: “All who desire to lead a new life, to give their hearts to God and go to heaven, will stand.” Quite a few stood up. Then the preacher raised his voice and roared: “All who do not wish to go to hell will stand.” All stood up except Mr Lincoln. Cartwright was quick to note the exception, and in solemn tones he said:

“I observe that many responded to the first invitation to give their hearts to God and go to heaven, and I further observe that all of you save one indicated you did not wish to go to hell. The sole exception is Mr Lincoln, who did not respond to either invitation. May I inquire of you, Mr Lincoln, where you are going?”

Lincoln rose slowly, the eyes of all upon him. “I came here,” he said, “as a respectful listener. I did not know I was to be singled out by Brother Cartwright; I believe in treating religious matters with due solemnity. I admit that the questions propounded by Brother Cartwright are important. I did not feel called upon to answer as the rest did. Brother Cartwright asks me directly where I am going. I desire to reply with equal directness: I am going to Congress!” 10

And so Lincoln did. He beat Cartwright by 1,511 votes.

Peter’s Preaching Style

Few examples remain of Peter’s preaching style, but probably the best was a short narrative written about him called “The Jocose 11 Preacher” from an eyewitness account of a camp meeting sometime in the 1830s. The story begins by telling of Peter arriving in the evening instead of the morning for a sermon because his horse fell injured. He could have left the horse and walked, but in a note to the awaiting group he explained, “Horses have no souls to save, and therefore it is all the more the duty of Christians to take care of their bodies.” 12 It was a beautiful late summer evening, and when he finally arrived,

They knew not . . . what to think or make of the man. His figure was tall, burly, massive, and seemed even more gigantic than the reality from its crowning foliage of luxuriant coal-black hair, wreathed into long, curling ringlets. Add a head that looked large as a half-bushel, beetling brows, and rough and craggy as fragmentary granite, irradiated at the base by eyes of dark fire, small and twinkling like diamonds in the sea - (they were diamonds of a soul shining in a measureless sea of humour,) a swarthy complexion, as if embrowned by the kisses of sunbeams, a fixedness of purpose in the expression of the mouth, with rich, rosy lips, always slightly parted as if wearing a perpetual and merry smile, and you have a life-like portrait of Peter Cartwright, the far-famed Methodist Residing Elder. 13

As the singing finished, a hush fell over the crowd and Peter began. Taking his text from Matthew 8:36, “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” - one of his favourites - he began. The eyewitness described it as “transcendent eloquence.” 14 He gave about fifteen minutes of a conversational introduction leading into a half-hour satirical parable of the folly of a sinner. From here he descended into a dramatic description of the horrors of hell itself and then ascended to a triumphant picture of the joys of heaven awaiting those who turned to the Lord.

The audience was visibly moved. “Five hundred, many of them until that night infidels, rushed forward and prostrated themselves upon their knees. The meeting was continued for two weeks, and more than a thousand converts were added to the church.”15 Thus was the power of a Peter Cartwright sermon.

Peter’s Final Years

In 1856, Peter released his Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, The Backwoods Preacher, and the book became a bestseller in one of the greatest decades of American literature alongside Melville’s Moby Dick, Thoreau’s Walden, Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. The book is still popular today as a wonderful portrait of frontier life, the Kentucky camp meetings, and Peter’s remarkable stories of preaching and living on the Wild West of the early 1800s. It is hard to come away from reading it without feeling that Peter was indeed a legend of a time in America when the “West” was still east of the Mississippi. This was not his only book, he also wrote Fifty Years as a Residing Elder (1871) among others.

Peter finally retired from circuit riding in 1869. Evidence points to the fact that Peter ended his days virtually senile in a struggle over selling some land they felt he was selling only because he had lost his mind. Before they could take legal action though, on September 25, 1872, Peter passed away at 3 o’clock in the afternoon of unknown causes just a few weeks past his eighty-seventh birthday.

Works Consulted

- Robert Bray, Peter Cartwright, Legendary Frontier Preacher (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 7.

- Peter Cartwright, Autobiography of Peter Cartwright, The Backwoods Preacher, ed. W. P. Strickland (Cincinnati: Cranston and Curts, 1856), 27.

- Ibid., 34-38.

- Ibid., 134.

- Ibid., 98.

- Ibid., 111.

- Bray, Peter Cartwright, 54.

- Peter Cartwright, Fifty Years as a Presiding Elder (Cincinnati: Hitchcock and Walden, 1871), 217, in Bray, Peter Cartwright, 54.

- Cartwright, Autobiography, 128.

- Edgar De Witt Jones, Lincoln and the Preachers (Salem, NH: Ayer Publishing, 1970), 44.

- Means “with a playfully joking disposition.”

- “Rev. Peter Cartwright, the Methodist Presiding Elder. A Genuine Portrait from “Life in Illinois,’” Southern and South-Western Sketches, 6-7, in Bray, Peter Cartwright, 153.

- “Rev. Cartwright . . . ,” 7-8, in Bray, Peter Cartwright, 153-4.

- “Rev. Cartwright . . . ,” 11, in Bray, Peter Cartwright, 154.

- “Rev. Cartwright. . . ,” 11, in Bray, Peter Cartwright,154.

Receive a periodical newsletter about this Author. Links in connection with Articles related to this Author will be periodically sent to your email.

Related Topics : Generals Of God, Roberts Liardon, Peter Cartwright,

At IUSEFAITH.com and JUTILISELAFOI.COM, we are dedicated to curating and delivering powerful devotionals from genuine, Spirit-led men and women of God. Through reading, analysis, translation, programming, and occasionally content generation, we ensure you receive rich, faith-building resources.

To continue expanding this work and reaching more souls, we are upgrading to a higher hosting plan. If you are led to support this Kingdom mission, kindly reach out via +233 552 524 195 to learn how you can contribute.

Together, let’s advance the Gospel through technology.