with voice

commands, please use

the Chrome browser on PC

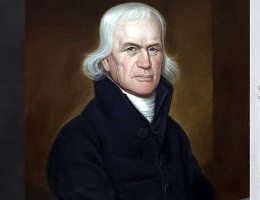

James McGready and the Kentucky Revivals

Date of Birth: 1763.

Fell As Sleep in The Lord: February, 1817.

Marriage: 1790.

Children: UnknownAbout this time, a remarkable spirit of prayer and supplication was given to Christians and a sensible, heart-felt burden of the dreadful state of sinners out of Christ: so that it might be said with propriety, that Zion prevailed in birth to bring forth her spiritual children.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, America experienced its first Pentecost in the summers of 1800 and 1801 in the newly formed states of Kentucky and Tennessee. It was a time that would set the American frontier on fire for God and make the Gospel the common language of the nation from the settlements on the Atlantic seaboard to the Mississippi River.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, America experienced its first Pentecost in the summers of 1800 and 1801 in the newly formed states of Kentucky and Tennessee. It was a time that would set the American frontier on fire for God and make the Gospel the common language of the nation from the settlements on the Atlantic seaboard to the Mississippi River.

Central to this move of God was James McGready, a Scotch-Irish Presbyterian minister born in Pennsylvania in 1763. When he was very young, James’ parents moved to Guilford County, North Carolina, where he grew up and attended David Caldwell’s academy. He returned to Pennsylvania for college and seminary at Cannonsburg near Pittsburgh (the institution later became part of Washington and Jefferson College). Here he would hear Dr. John Blair Smith recount the history of a powerful revival he had experienced in Virginia. James immediately grew fascinated with the subject of revival.

He was licensed as a minister by the Presbytery of Redstone on August 13, 1788 and married sometime around 1790. He pastored a congregation in Orange County, North Carolina for a while, which was not far from Guilford. He quickly gained notoriety in the area “for his effective preaching . . . and for his intense moral seriousness. He touched people by his prayers and sermons, and at the same time troubled them by his denunciation of anything less than perfect holiness in conduct.” 1 From time to time he would minister at Caldwell’s academy where he had been educated, and there touched the lives of future revivalists. Among them was William Hodge, who would become a protégé of James, and Barton Stone, who would be the pastor at Cane Ridge during the 1801 camp meeting there. Stone would later say of McGready:

Such earnestness - such zeal - such powerful persuasion, enforced by the joys of heaven and miseries of hell, I had never witnessed before. My mind was chained by him, and followed him closely in his rounds of heaven, earth, and hell, with feelings indescribable. His concluding remarks were addressed to the sinner to flee the wrath to come without delay. Never before had I comparatively felt the force of truth. Such was my excitement, that had I been standing, I should have probably sunk to the floor under the impression. 2

Heading West

In 1796 James left North Carolina for Kentucky and became the pastor for three congregations in Logan County near the communities of Red River, Gaspar River, and Muddy River. There he continued to call for moral excellence on one of the roughest parts of the frontier. The region was known as “Rogue’s Harbor” for those who had fled there to escape the long arm of the law east of the Alleghenies. It was an area rampant with vice and alcoholism, land grabbing, and homesteaders trying to bring civilization to a land never before tamed. Christianity also seemed on the ropes as Universalism and Deism were on the rise. As Methodist minister James Smith put it in 1795, “the Universalists, joining with the Deists, had given Christianity a deadly stab hereabouts.” 3 The 1790s were actually seeing a decline in church attendance in Kentucky and Tennessee. In 1798 the Presbyterian General Assembly decreed a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer to call for the redemption of the frontier from “Egyptian darkness.” 4 With them, Rev. McGready began earnestly praying for revival to sweep the two new states.

In May of 1797, Rev. McGready saw the first visit of the Holy Spirit as he preached. One of the women who had been a faithful part of the church “was struck with deep conviction,” sought salvation anew, “and in a few days was filled with joy and peace in believing.” In a letter to a friend of October 23, 1801, McGready went on to describe what happened next:

She immediately visited her friends and relatives, from house to house, and warned them of their danger in a most solemn, faithful manner, and plead with them to repent and seek religion. This . . . was accompanied with the divine blessing [manifestations of the Holy Spirit] to the awakening of many. About this time the ears of all in that congregation seemed to be open to receive the word preached, and almost every sermon was accompanied with the power of God, to the awakening of sinners. During the summer about ten persons in the congregation were brought to Christ. 5

The seeds of revival were starting to sprout.

The Annual Communions

Ever looking for opportunities to spur renewal in the hearts of his congregation, James adopted a formula that had sparked a revival in Ulster (Northern Ireland) and Scotland, the greatest of which had been at Cambuslang in 1742 where George Whitefield had ministered to crowds as large as 30,000. McGready called for a multi-day communion service. Families from the surrounding areas would come to stay with a family in town, and meetings would start Friday evening. Services would continue on through Saturday and Sunday, then there would be a Monday morning service with communion being taken around noontime. This proved a good formula for the sparsely populated Logan County. Scattered settlers were able to come together as a community to receive the sacrament, which was otherwise impractical on a weekly, or even monthly, basis because of the travel times.

These became annual events in McGready’s churches - as they probably had been in North Carolina as well - but were anything but routine after the services at Gaspar River in July of 1798. Again, in McGready’s own words:

On Monday the Lord graciously poured out his Spirit; a very general awakening took place - perhaps but few families in the congregation could be found who, less or more, were not struck with an awful sense of their lost estate. During the week following but few persons attended to worldly business, their attention to the business of their souls was so great. On the first Sabbath of September, the sacrament was administered at Muddy River. . . . At this meeting the Lord graciously poured forth his spirit, to the awakening of many careless sinners. Through these two congregations already mentioned, and through Red River, my other congregation . . . awakening work went on with power under every sermon. The people seemed to hear, as for eternity. In every house, and almost in every company, the whole conversation with people, was about the state of their souls. 6

As a New Century Dawned

The first Communion of the summer of 1799 took place at Red River in July. Keeping with the formula at Cambuslang, James welcomed other ministers including the Presbyterians John Rankin, William Hodge, and William McGee, and William’s Methodist brother, John McGee. McGready described what happened in a letter he wrote in 1801:

On Monday the power of God seemed to fill the congregation; the boldest, daring sinners in the country covered their faces and wept bitterly. After the congregation was dismissed, a large number of people stayed about the doors, unwilling to go away. Some of the ministers proposed to me to collect the people in the meetinghouse again, and perform prayer with them; accordingly, we went in and joined in prayer and exhortation. The mighty power of God came amongst us like a shower from the everlasting hills - God’s people were quickened and comforted; yea, some of them were filled with joy unspeakable, and full of glory. Sinners were powerfully alarmed, and some precious souls were brought to feel the pardoning love of Jesus. 7

Again similar things followed in the Gaspar and Muddy River congregations - but God was far from done.

The following summer, James called for the Red River Communion to take place earlier in the year, on the weekend of Saturday, June 21 to Monday, June 23, 1800. Roughly five hundred people attended. Rev. McGready invited the same group of ministers as the year before, but this time the results were beyond expectations as the Holy Spirit showed up with power. As McGready recalled:

In June the sacrament was administered at Red River. This was the greatest time we had ever seen before. As multitudes were struck down under awful conviction; the cries of the distressed filled the whole house. There you might see profane swearers, and sabbath breakers pricked to the heart, and crying out, “What shall we do to be saved?” There are frolickers, and dancers crying for mercy. There you might see little children of ten, eleven, and twelve years of age praying and crying for redemption, in the blood of Jesus, in agonies of distress. During this sacrament, and until the Tuesday following, ten persons we believe, were savingly brought home to Christ. 8

The eruption at Red River was truly unexpected the first three days, which passed with little remarkable happening. The services had been reverent and orderly. During Monday morning’s service though, as William Hodge preached a moving message on Job 22:21 - ”Acquaint now thyself with him, and be at peace: thereby good shall come unto thee” - a woman who had been seeking assurance of her salvation for some time began shouting and singing. Then, after a short intermission, John McGee rose to speak, and came to the pulpit singing,

Come Holy Spirit, heavenly dove,

With all thy quick’ning powers,

Kindle a flame of sacred love

In these cold hearts of ours. 9

At this, at least one other woman cried out, probably also coming to a sudden knowledge of saving grace. McGee descended to congratulate them, and as he did, the glory of God broke out over the people. Some fell to the ground, others cried out for mercy, others prayed, and others began praising God at the top of their voices. William McGee, who was sitting nearby, rose to go to the pulpit but collapsed onto the floor before it. As John McGee turned to him, he felt the power of God fall so heavily that he nearly crumbled beside his brother. John later recalled,

I turned to go back and was near falling; the power of God was strong upon me. I turned again, and, losing sight of the fear of man, I went through the house shouting and exhorting with all possible ecstasy and energy, and the floor was soon covered with the slain. 10

Unsure of what was happening as they had never seen people fall to the ground before as they preached, McGready, Hodge, and Rankin wondered if they should intervene. McGee, however, a “shouting Methodist” himself, assured them that this was the work of God, and they let the service run its course. Rev. Rankin later reported:

On seeing and feeling his confidence, that it was the work of God, and a mighty effusion of his spirit, and having heard that he was acquainted with such scenes in another country, we acquiesced and stood in astonishment, admiring the wonderful works of God. When this alarming occurrence subsided in outward show, the united congregation returned to their respective abodes, in contemplation of what they had seen, heard, and felt on this most oppressive occasion. 11

The Revival Grows

The ministers then decided to have another Communion the following month at the Gaspar River Meetinghouse. The McGee brothers went to speak someplace different almost every weekend that summer and such meetings truly caught on like wildfire. The word spread quickly, and momentum gathered towards the Gaspar River Communion. As Rankin remarked,

The news of the strange operations which had transpired at the previous meeting had run throughout the country in every direction, carrying a high degree of excitement to the minds of almost every character. The curious came to gratify their curiosity. The seriously convicted, presented themselves that they might receive some special and salutary benefit to their souls, and promote the cause of God, at home and abroad. 12

In his Narrative, McGready describes how the Kentucky revival truly took hold in Gaspar, drawing people from far and wide:

In July the sacrament was administered in Gasper River Congregation. Here multitudes crowded from all parts of the country to see a strange work, from the distance of forty, fifty, and even a hundred miles; whole families came in their wagons; between twenty and thirty wagons were brought to the place, loaded with people, and their provisions, in order to encamp at the meeting-house. . . . Of many instances to which I have been an eyewitness, I shall only mention one, viz. A little girl. I stood by her whilst she lay across her mother’s lap almost in despair. I was conversing with her when the first gleam of light broke in upon her mind - She started to her feet, and in an ecstasy of joy, she cried out, “O he is willing, he is willing - he is come, he is come - O what a sweet Christ he is - O what a precious Christ he is - O what a fulness I see in him - O what a beauty I see in him - O why was it that I never could believe! That I never could come to Christ before, when Christ was so willing to save me?” Then turning round, she addressed sinners, and told them of the glory, willingness, and preciousness of Christ, and plead with them to repent; and all this in language so heavenly, and, at the same time, so rational and scriptural, that I was filled with astonishment. But were I to write you every particular of this kind that I have been an eye and ear witness to, during the two past years, it would fill many sheets of paper. 13

As a result of the numbers, the Gaspar River meeting house proved too small to hold the crowds, so areas where cleared to hold meetings in the open air. A “preaching stand” was constructed as were log pews. Services ran through the entirety of the first night and the cries of the penitent threatened to drown out the voice of John McGee as he spoke on Sunday. The same signs of the move of the Spirit that had been at Red River were at Gaspar River - people falling under the power of God, those crying out and praying under the conviction of the Spirit, as well as the loud cries of joy and praise from those who found the peace with God they had come to receive.

The Camp Meeting Was Born

Most consider Gaspar River to be the first camp meeting ever held, though the term would not be coined for another year or two. This would happen because the Communions began to draw crowds larger than could be housed with local families, and would soon outgrow the capacities of the meetinghouses to hold everyone.

The conviction of the Spirit showed no limits either, as believers, Universalists, Deists, and even Atheists were all struck down alike. Revival fire spread out from Logan County throughout Kentucky and Tennessee. Communions were held almost every weekend for the rest of the summer.

At this sacrament a great many people from Cumberland, particularly from Shiloh Congregation, came with great curiosity to see the work, yet prepossessed with strong prejudices against it; about five of whom, I trust, were savingly and powerfully converted before they left the place. A circumstance worthy of observation, they were sober professors in full communion. It was truly affecting to see them lying powerless, crying for mercy, and speaking to their friends and relations, in such language as this: “O, we despised the work that we heard of in Logan; but, O, we were deceived - I have no religion; I know now there is a reality in these things: three days ago I would have despised any person that would have behaved as I am doing now; but, O, I feel the very pains of hell in my soul.” . . . When they went home, their conversation to their friends and neighbors, was the means of commencing a glorious work that has overspread all the Cumberland settlements to the conversion of hundreds of precious souls. The work continued night and day at this sacrament, whilst the vast multitude continued upon the ground until Tuesday morning. According to the best computation, we believe that forty-five souls were brought to Christ on this occasion. 14

As 1800 drew to a close, God’s presence was surely falling on Kentucky and Tennessee, but they had not seen anything yet - a fresh dose of Pentecost was just around the corner. The next year, 1801, would see roughly fifty different congregations plan four-day Communions between May and November, the largest and most explosive of all would be at Cane Ridge in August. (See “Barton Stone and the Cane Ridge Revival” for more on this.)

Revival Fires Quenched

Those who tried to fit the works of God of this summer into some kind of man-made doctrinal box would see no more of such manifestations. Other groups would leave their denominations and form new ones in order to continue chasing these “exercises of the Spirit,” but miss out on the heart of God by chasing the spectacular rather than God Himself. The Cumberland valley congregations broke off from mainline Presbyterianism to become the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Notably, however, James McGready refused to leave the mainline Presbyterians, and never became part of the Cumberland group. However, he stayed in contact and fellowship with them in the years to come. James never left Kentucky.

James attended a Cumberland Presbyterian camp meeting near Evansville, Indiana, in t he fall of 1816. After ministering, he had prayed with those seeking salvation, and he proclaimed, “O blessed be God! I this day feel the same holy fire that filled my soul sixteen years ago, during the glorious revival of 1800.” He encouraged the other minister there, “Brethren, go on, God is with you, be humble, and he will continue to bless you.”

He returned to his congregation in Henderson County and told them, “Brethren, when I am dead and gone, the Cumberland Presbyterians will come among you and occupy this field; go with them, they are a people of God.” While he lived no Cumberland preacher operated near his congregations out of respect for him. James McGready died in Henderson in February of 1817.

Works Consulted

- Paul K. Conkin, Cane Ridge: America’s Pentecost (Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 53.

- Barton Stone, A Short History of the Life of Barton W. Stone, 1847, Chapter 2, http://www.mun.ca/rels/restmov/texts/bstone/barton.html.

- Mark Galli, “Revival at Cane Ridge,” Christian History 14, no. 1 [Issue 45] (1995): 11.

- Ibid., 11.

- James McGready, “Narrative of the Commencement and Progress of the Revival of 1800 in a Letter to a Friend dated October 23, 1801,” Historical Foundation of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

and the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in America, http://www.cumberland.org/hfcpc/McGreaBK.htm#anchor222019. - Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- T. Marshall Smith, Legends of the War of Independence (Louisville, KY: J. F. Brennan, Publisher, 1855), 372-373, in Kenneth O. Brown, Holy Ground: A Study of the American Camp Meeting (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1992), 18. The hymn, “Come, Holy Spirit, Heavenly Dove,” was written by Isaac Watts, and was widely sung by Methodists.

- John McGee to Douglas, Methodist Magazine, 4: 190, in John B. Boles, The Great Revival: Beginnings of the Bible Belt (Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1972), 54.

- John Rankin, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 1845, in John Patterson MacLean, Shakers of Ohio: Fugitive Papers Concerning the Shakers of Ohio, With Unpublished Manuscripts (Columbus, OH: The F. J. Heer Printing Company, 1907), 57.

- John Rankin, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 280-281, in John B. Boles, The Great Revival: Beginnings of the Bible Belt (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1972), 55.

- McGready, “Narrative of the Commencement and Progress of the Revival of 1800.”

- Ibid.

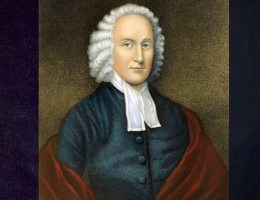

"Barton Stone and the Cane Ridge Revival"

Cane Ridge, Kentucky, August 6-11, 1801

Kentucky was ablaze with a revival at the turn of the nineteenth century. So when Barton Stone heard that God was moving at James McGready’s Communions in Logan County Kentucky in 1800, he decided to attend one the following spring. The scene that greeted him was revolutionary. By then the crowds attracted by these multi-day Communion gatherings had grown too large to have services all in one place at one time, so various areas of ministry began taking place concurrently. In his autobiography, Rev. Stone described what he experienced:

The scene to me was new and passing strange. It baffled description. . . . Many, very many fell down, as men slain in battle, and continued for hours together in an apparently breathless and motionless state - sometimes for a few moments reviving, and exhibiting symptoms of life by a deep groan, or piercing shriek, or by a prayer for mercy most fervently uttered. After lying thus for hours, they obtained deliverance. The gloomy cloud, which had covered their faces, seemed gradually and visibly to disappear, and hope in smiles brightened into joy - they would rise shouting deliverance, and then they would address the surrounding multitude in language truly eloquent and impressive. With astonishment did I hear men, women, and children declaring the wonderful works of God, and the glorious mysteries of the gospel. Their appeals were solemn, heart-penetrating, bold and free. Under such addresses, many others would fall down into the same state from which the speakers had just been delivered. 1

While he might have been sceptical that such experiences were genuine, he knew some of the “slain” personally, so there was no room for doubt. When he returned to his congregations at Cane Ridge and Concord, he shared some of what he saw and his parishioners were struck to the heart. At Cane Ridge, “The congregation was affected with awful solemnity, and many returned home weeping.” At Concord, “two little girls were struck down under the preaching of the word, and in every respect were exercised as those were in the south of Kentucky.” 2 Upon returning to Cane Ridge, he found many seeking salvation with new vigour. A good friend, Nathaniel Rogers, greeted him by praising the Lord as he had just gained the assurance of his own salvation. Then, an even more interesting scene emerged:

We hurried into each others’ embrace, he [Nathaniel Rogers] still praising the Lord aloud. The crowd [that had been seeking the Lord while awaiting Reverend Stone’s return] left the house and hurried to this novel scene. In less than twenty minutes, scores had fallen to the ground - paleness, trembling, and anxiety appeared in all - some attempted to fly from the scene panic-stricken, but they either fell or returned immediately to the crowd, as unable to get away. In the midst of this exercise, an intelligent deist in the neighbourhood, stepped up to me, and said, “Mr Stone, I always thought before that you were an honest man; but now I am convinced you are deceiving the people.” I viewed him with pity, and mildly spoke a few words to him - immediately he fell as a dead man and rose no more till he confessed the Saviour. The meeting continued on that spot in the open air, till late at night, and many found peace in the Lord. 3

After these events, Stone scheduled a Communion in Cane Ridge for the first weekend of August, only a month after he married. Expecting impressive numbers, and knowing that the meetinghouse could seat 350 and hold no more than 500, areas were cleared and a large tent erected as secondary places of ministry.

Unexpected Numbers

On Friday, August 6, wagons of families began arriving. Hundreds soon turned into thousands, and local families housing the attendees - even the richer ones who might house three or four families - were soon swamped to overflowing. With no organization that could hold those numbers, the scene passed somewhere between the absolute chaos of a refugee camp and the Christian equivalent of the Feast of Tabernacles. In his autobiography, Rev. Stone tried to describe the scene that quickly began to spread over several acres:

The roads were literally crowded with wagons, carriages, horsemen, and footmen, moving to the solemn camp. The sight was affecting. It was judged, by military men on the ground, that there were between twenty and thirty thousand collected. Four or five preachers were frequently speaking at the same time, in different parts of the encampment, without confusion. The Methodist and Baptist preachers aided in the work, and all appeared cordially united in it - of one mind and one soul, and the salvation of sinners seemed to be the great object of all. We all engaged in singing the same songs of praise - all united in prayer - all preached the same things - free salvation urged upon all by faith and repentance. A particular description of this meeting would fill a large volume, and then the half would not be told. The numbers converted will be known only in eternity. . . . This meeting continued six or seven days and nights, and would have continued longer, but provisions for such a multitude failed in the neighbourhood. 4

Building Up and Overflowing

It had rained the first Friday evening, so the numbers were smaller, but the meetinghouse was still filled to overflowing. Pastor Stone gave the opening address and Matthew Houston gave the first sermon to a very expectant audience. Nothing remarkable happened that evening, though some remained in prayer throughout the night.

Saturday morning was still quiet as the services continued, but by noon more families where arriving, and they were doing so by the thousands despite the intermittent rain. Single men who could more easily come in on horseback during the day were staying in taverns or sleeping in barns as far away as Lexington - a distance of some twenty-five miles. The center could no longer hold, there were simply too many bodies to keep in one area. By the afternoon, both the meetinghouse and the tent were filled to overflowing and the preaching continued without interruption. It wasn’t long, however, before preaching began breaking out wherever crowds were gathered. It was said that over the weekend there were times when as many as seven preachers were preaching to large crowds all at the same time. The numbers swelled to tens of thousands in the following hours, and at the high point of the attendance, one tally had that 1,143 wagons and similar vehicles had set up camp in the area. These were extraordinary numbers considering that Lexington only had a population of 1,795 at the time, and there were fewer than 250,000 people in all of Kentucky. 5

Touched by the Holy Spirit

In one of the gatherings, a young minister named Richard Nemar exclaimed he had found a “true new gospel” and it was as if electricity shot through the crowd. Though no one was quite sure what he meant by this - some were even shocked and offended - the Holy Spirit fell in the midst of the congregation. Rev. Stone kept a careful record of all the manifestations over the weekend and included the following account of some of them:

The bodily agitations or exercises, attending the excitement in the beginning of this century, were various, and called by various names - as, the falling exercise - the jerks - the dancing exercise - the barking exercise - the laughing and singing exercise, etc. The falling exercise was very common among all classes, the saints and sinners of every age and of every grace, from the philosopher to the clown. The subject of this exercise would, generally, with a piercing scream, fall like a log on the floor, earth, or mud, and appear as dead. Of thousands of similar cases, I will mention one. At a meeting, two . . . sisters, were standing together attending to the exercises and preaching. . . . Instantly they both fell, with a shriek of distress, and lay for more than an hour apparently in a lifeless state. Their mother, a pious Baptist, was in great distress, fearing they would not revive. At length they began to exhibit symptoms of life, by crying fervently for mercy, and then relapsed into the same death-like state, with an awful gloom on their countenances. After awhile, the gloom on the face of one was succeeded by a heavenly smile, and she cried out, “Precious Jesus,” and rose up and spoke of the love of God - the preciousness of Jesus, and of the glory of the gospel, to the surrounding crowd, in language almost superhuman, and pathetically exhorted all to repentance. In a little while after, the other sister was similarly exercised. From that time they became remarkably pious members of the church. . . .

The jerks cannot be so easily described. Sometimes the subject of the jerks would be affected in someone member of the body, and sometimes in the whole system. When the head alone was affected, it would be jerked backwards and forward, or from side to side, so quickly that the features of the face could not be distinguished. When the whole system was affected, I have seen the person stand in one place, and jerk backwards and forward in quick succession, their head nearly touching the floor behind and before. All classes, saints and sinners, the strong as well as the weak, were thus affected. I have inquired of those thus affected. They could not account for it, but some have told me that those were among the happiest seasons of their lives. I have seen some wicked persons thus affected, and all the time cursing the jerks, while they were thrown to the earth with violence. Though so awful to behold, I do not remember that any one of the thousands I have seen ever sustained an injury in the body. This was as strange as the exercise itself. . . .

The barking exercise, (as opposers contemptuously called it,) was nothing but the jerks. A person affected with the jerks, especially in his head, would often make a grunt, or bark, if you please, from the suddenness of the jerk. This name of barking seems to have had its origin from an old Presbyterian preacher of East Tennessee. He had gone into the woods for private devotion and was seized with the jerks. Standing near a sapling, he caught hold of it, to prevent his falling, and as his head jerked back, he uttered a grunt or kind of noise similar to a bark, his face being turned upwards. Some wag discovered him in this position and reported that he found him barking up a tree.

The laughing exercise was frequent, confined solely with the religious. It was a burst of loud, hearty laughter, but one sui generis [“of its own kind”]; it excited laughter in none else. The subject appeared rapturously solemn, and his laughter excited solemnity in saints and sinners. It is truly indescribable.

The running exercise was nothing more than, that persons feeling something of these bodily agitations, through fear, attempted to run away, and thus escape from them; but it commonly happened that they ran not far, before they fell, or became so greatly agitated that they could proceed no farther. I knew a young physician of a celebrated family, who came to some distance to a big meeting to see the strange things he had heard of. He and a young lady had sportively agreed to watch over, and take care of each other if either should fall. At length the physician felt something very uncommon, and started from the congregation to run into the woods; he was discovered running as for life but did not proceed far till he fell down, and there lay till he submitted to the Lord, and afterwards became a zealous member of the church. Such cases were common. 6

Estimates of those touched by the Holy Spirit ranged from five hundred to a thousand at a time.

Another Eyewitness Account

Among those in the audience were some detractors, of whom Robert W. Finley was one, even though he was the son of the builder of the Cane Ridge Meetinghouse, Rev. James B. Finley. (James B. was also a successful circuit rider who had a powerful ministry among the Wyandot Indians of Ohio.) This is what he had to say of the events:

On the way to the meeting I said to my companions, “If I fall, it must be by physical power, and not by singing and praying,” and as I prided myself upon my manhood and courage, I had no fear of being overcome by any nervous excitability or being frightened into religion. We arrived upon the ground, and here a scene presented itself to my mind not only novel and unaccountable but awful beyond description. A vast crowd, supposed by some to have amounted to twenty-five thousand, was collected together. The noise was like the roar of Niagara.

The vast sea of human beings seemed to be agitated as if by a storm. I counted seven ministers, all preaching at one time; some on stumps, others in wagons, and one - the Reverend William Burke, now of Cincinnati - was standing on a tree which had in falling lodged against another. Some of the people were singing, others praying, some crying for mercy in the most piteous accents, while others were shouting most vociferously.

While witnessing these scenes a peculiarly strange sensation, such as I had never before felt, came over me. My heartbeat tumultuously, my knees trembled, my lips quivered, and I felt as though I must fall to the ground. . . . I became so weak and powerless that I found it necessary to sit down.

Soon after I left and went into the woods, and there I strove to rally and man up my courage. I tried to philosophize in regard to these wonderful exhibitions, resolving them into mere sympathetic excitement, a kind of religious enthusiasm, inspired by songs and eloquent harangues. My pride was wounded, for I had supposed that my mental and physical strength and vigour could most successfully resist these influences.

After some time I returned to the scene of excitement, the waves of which, if possible, had risen still higher. The same awfulness of feeling came over me. I stepped upon a log, where I could have a better view of the surging sea of humanity. The scene that then presented itself to my mind was indescribable. At one time I saw at least five hundred swept down in a moment, as if a battery of a thousand guns had been opened upon them, and then immediately followed shrieks and shouts that rent the very heavens. My hair rose up on my head, my whole frame trembled, the blood ran cold in my veins, and I fled for the woods a second time, and wished I had stayed at home. . . .

In this state, I wandered about from place to place, in and around the encampment. At times it seemed as if all the sins I had ever committed in my life were vividly brought up in array before my terrified imagination, and under their awful pressure, I felt as if I must die if I did not get relief. My heart was so proud and hard that I would not have fallen to the ground for the whole State of Kentucky. I felt that such an event would have been an everlasting disgrace and put a final quietus on my boasted manhood and courage. . . .

Then came from my streaming eyes the bitter tears, and I could scarcely refrain from screaming aloud. Night approaching, we put up near Mayslick, the whole of which was spent by me in weeping and promising God if he would spare me till morning I would pray and try to mend my life and abandon my wicked courses. 7

Robert Finley went on to become a lifelong minister of some importance in the Methodist Church.

Evenings at Cane Ridge

As evening descended, campfires were lit and candles, lamps, and torches provided the light as the services continued into the night. This light playing on the trees must have created a wondrous atmosphere for renewed reverence. Another witness had the following testimony about what the evenings were like:

The spectacle presented at night was one of the wildest grandeur. The glare of the blazing campfires falling on a dense multitude of heads simultaneously bowed in adoration and reflected back from the long-range of tents upon every side, hundreds of lamps and candles suspended among the trees, together with numerous torches flashing to and fro, throwing an uncertain light upon the tremulous foliage and giving an appearance of dim and indefinite extent to the depths of the forest; the solemn chanting of hymns, swelling and falling on the night winds; the impassioned exhortations, the earnest prayers, the sobs, the shrieks or shouts bursting from persons under the agitation of mind; the sudden spasms which seized upon and unexpectedly dashed them to the ground - all conspired to invest the scene with terrific interest, and arouse their feelings to the highest state of excitement. 8

Thousands Saved

The communion service had been planned for Sunday instead of Monday as it always was at other such gatherings, and came off as planned. The tables for this were set up in the meetinghouse in the shape of a cross and could serve as many as a hundred people at a time. Estimates range from between 800 and 1,100 for those who actually took part as only those recognized as converts were allowed to partake of it.

As the people exited the communion services, a vast number of small prayer groups began forming, and literally, hundreds began spontaneously exhorting anyone within earshot as the Spirit of God fell on them. This was the most remarkable manifestation of Cane Ridge, as these exhorters could be men, women, illiterate people, African Americans, children, or people known for their shyness. Because of such sights, camp meetings would soon earn the title “carnival of preachers” as one could literally walk among them and hear preachers from all sides.

One seven-year-old girl named Barbara climbed upon a man’s shoulder and began to speak words much beyond her years until she was near exhaustion and settled down to rest her head on the man’s head as if falling asleep. When a tenderhearted man nearby remarked “Poor thing, she had better be laid down,” she revived immediately to proclaim, “Don’t call me poor, for Christ is my brother, God my father, and I have a kingdom to inherit, and therefore do not call me poor, for I am rich in the blood of the Lamb!” 9

As many packed their belongings to return home on Monday, others were just beginning to show up to experience the outpouring. Prayer, preaching, exhorting, singing, and manifestations of the Holy Spirit would continue until Thursday of that week. Estimates of those who were touched with “exercises of the Spirit” ranged between 1,000 to 3,000 - the same numbers were estimated for how many were converted over the course of the meeting.

Cane Ridge was the high point of the Kentucky Revival but was far from exclusive. 1801 was a year of “boiling-hot religion.” Such manifestations of the Holy Spirit would continue through the rest of the summer of 1801. Kentucky and the young United States would be forever changed. The camp meeting set the precedent for America being seen as an “evangelical nation.”

- Barton Stone, A Short History of the Life of Barton W. Stone, 1847, Chapter 5, http://www.mun.ca/rels/restmov/texts/bstone/barton.html#ch_five.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ray A. Billington, Westward Expansion (New York, 1949), 250, in Bernard A. Weisberger, They Gathered at the River: The Story of the Great Revivalists and their Impact upon Religion in America (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1958), 31.

- Barton Stone, A Short History of the Life of Barton W. Stone, 1847, Chapter 6, http://www.mun.ca/rels/restmov/texts/bstone/barton.html#ch_six. [Inserts added.]

- Robert W. Finley in James R. Rodgers, The Cane Ridge Meeting-House (Cincinnati, OH: The Standard Publishing House, 1910), 59-62.

- Davidson in Rodgers, The Cane Ridge Meeting-House, 56.

- Letter from a man to his sister, August 10, 1801, http://www.mun.ca/rels/restmov/texts/accounts/letter8.html.

Receive a periodical newsletter about this Author. Links in connection with Articles related to this Author will be periodically sent to your email.

Related Topics : Generals Of God, Roberts Liardon, James McGready,

At IUSEFAITH.com and JUTILISELAFOI.COM, we are dedicated to curating and delivering powerful devotionals from genuine, Spirit-led men and women of God. Through reading, analysis, translation, programming, and occasionally content generation, we ensure you receive rich, faith-building resources.

To continue expanding this work and reaching more souls, we are upgrading to a higher hosting plan. If you are led to support this Kingdom mission, kindly reach out via +233 552 524 195 to learn how you can contribute.

Together, let’s advance the Gospel through technology.