with voice

commands, please use

the Chrome browser on PC

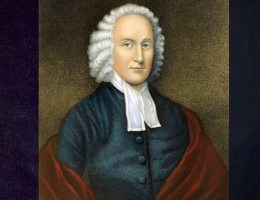

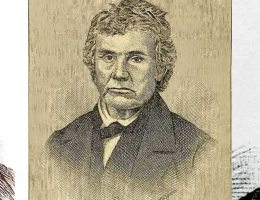

Francis Asbury

Date of Birth : August 20, 1745.

Fell As Sleep in The Lord : March 31, 1816.

Marriage : Never married.

Children : 0We should so work as if we were to be saved by our works; and so rely on Jesus Christ, as if we did no works.

On the frontier of scattered homesteads and small towns of the newborn United States that stretched towards the Mississippi River, the news was scarce and churches even scarcer. Ministers of the time were concentrated in the large cities of the east, but Francis Asbury saw the importance of returning to the pattern set by the apostles when Jesus sent them out two by two. In his lifetime, Asbury “rode more than a quarter of a million miles on horseback and crossed the Allegheny Mountains some sixty times . . . Asbury stayed in 10,000 households and preached 17,000 sermons.” 2 Rather than speaking to record-breaking crowds in city commons, the Methodist Circuit Riders - of which Asbury was a chief model - took revival to the farthest reaches of the frontier and became the threads that wove Americans together as a people.

On the frontier of scattered homesteads and small towns of the newborn United States that stretched towards the Mississippi River, the news was scarce and churches even scarcer. Ministers of the time were concentrated in the large cities of the east, but Francis Asbury saw the importance of returning to the pattern set by the apostles when Jesus sent them out two by two. In his lifetime, Asbury “rode more than a quarter of a million miles on horseback and crossed the Allegheny Mountains some sixty times . . . Asbury stayed in 10,000 households and preached 17,000 sermons.” 2 Rather than speaking to record-breaking crowds in city commons, the Methodist Circuit Riders - of which Asbury was a chief model - took revival to the farthest reaches of the frontier and became the threads that wove Americans together as a people.

Francis Asbury, or “Franky,” as he was called in his early years, was born in Hamstead Bridge, Staffordshire, England, not far from Birmingham. He was the only surviving child of Joseph and Elizabeth Asbury, who became committed Methodists after the loss of an infant daughter, Sarah, before Francis’s birth. Francis’s mother was a somber and dedicated believer.

When Asbury was thirteen, a travelling shoemaker held prayer meetings in the area. Although the man was a Baptist, Elizabeth believed he was sincere, and she invited him to speak at the Methodist society meeting in their home. The man’s words excited young Francis’s heart about salvation. Not long afterwards, Alexander Mather, a Methodist circuit rider, was assigned to the Birmingham area. When young Francis heard Mather explain how a person could have freedom from sin, his heart was again moved to undertake a life of holiness.

The Methodist society meetings had an indelible impact on Asbury as he grew through his teenage years. He loved the hymns they sang but was especially impressed by the freedom with which the preachers prayed and spoke. Mathers, for example, prayed as if God were standing in the room. He preached from his heart without ever relying on notes. This would become the model for the type of American Methodism Asbury would spread everywhere he went.

The Making of a Preacher

Francis began preaching publicly when he was about fifteen - he simply read Scripture passages aloud and expounded upon them at his mother’s society meetings. From there, he began branching out to the homes of other Methodists. Mather took notice of him and appointed him a local lay preacher and youth leader. Between the ages of seventeen and twenty, Francis recorded that he went “almost every place within my reach for the sake of precious souls; preaching generally, three, four, and five times a week, and the same time pursuing my calling.” 3 When Francis was twenty-two, the Methodist Conference in England gave him a probationary license; one year later, he was assigned his own circuit.

At this time, the Wesley brothers had been receiving letters from American pastors calling for experienced ministers to come over and help with those converted in the revivals of George Whitefield and the other awakeners. So, at the Bristol Conference in August of 1771, John announced, “Our [American] brethren call aloud for help. Who is willing to go over and help them?” 4 The call touched Francis’s heart deeply, and he, along with Richard Wright, agreed to go. Francis set sail within a month on September 4, taking two blankets for a bed, some clothes, and ten pounds sterling that had been given to him by some friends. He distilled his own mission statement into these few words:

Whither am I going? To the New World. What to do? To gain honour? No, if I know my own heart. To get money? No: I am going to live to God and to bring others so to do. 5

When I Saw the American Shore

The voyage was long for Asbury, who was often seasick. But he held to his calling - he preached on deck every afternoon he could, even if it meant tying himself to a mast in order to resist the pitching of the ship. When they docked in Philadelphia on Sunday, October 27, 1771, Asbury and Wright went to Saint George’s Church, the city’s Methodist headquarters, that very night. Asbury wrote:

The people looked on us with pleasure, hardly knowing how to show their love sufficiently, bidding us welcome with fervent affection and receiving us as angels of God. O that we may always walk worthy of the vocation wherewith we are called! When I came near the American shore my very heart melted within me to think from whence I came, and where I was going, and what I was going about. 6

After preaching for the first month in some of the largest churches in Philadelphia and New York, Asbury’s soul grew restless: “The preaching stops were enjoyable, but where was the evangelistic thrust to the countryside and to the more marginalized members of society?” 7 He wrestled with his frustration that the people in charge had not established any plans to spread the Gospel outside of New York and Philadelphia.

Soon, Francis persuaded two local churchmen to go with him to Westchester, New York, where he convinced the local judge to let him use the courthouse as his pulpit. It went so well that he returned two weeks later, and although the courthouse was not available, he simply set up a church at the home of the tavern owner. Asbury spent the night in the home of a local family who, when he invited them to pray after supper, became Methodists. Asbury would repeat this pattern of evangelism for the next forty-some years - he would find a place to preach, stay with a local family, and pray with those present to accept Christ. Each time he did, a new Methodist society would be born.

Methodist Drawbacks

Asbury’s first decade in America was marked by few such successes, however. The Methodist mission to America suffered from two major stumbling blocks. The first was that Methodism was inherently English, and tension between America and England was growing exponentially. All the Methodist leaders were men sent from England, and the societies were patterned after those in England, with their members still part of the Church of England. To make matters worse, John Wesley made the unfortunate choice of telling the colonists it was their Christian duty to seek reconciliation with the Crown.

The second obstacle was that Methodism could not find a home in the pluralistic Protestantism of the thirteen colonies. Why should one become a Methodist when the local Baptist or Congregational church had similar meetings already? In England, the formality of Anglicanism left a great deal of room during the rest of the week for the societies to meet. Churches in America, however, were much more open, with an emphasis on similar disciplines to those of the Methodists as opposed to the rituals of the sacraments. Methodism would have to break new ground as its own denomination before it could gather speed.

“I Am Determined Not to Leave Them”

As the tension with Great Britain continued to grow, so did Asbury’s allegiance to the colonies. The progression of his shifting allegiance is evident in his journal entries. In 1773, he wrote that the people were too disloyal to the mother country; in 1775, he penned, “Surely, the Lord will overrule and make all these things subservient to the spiritual welfare of his Church;” 8 by July 1776 he boldly proclaimed that the British would have little prospect of winning; and finally, in 1779, he prayed that God would “mercifully interpose for the deliverance of our land.” 9 By the spring of 1780, Asbury was a recognized citizen of Delaware.

In August 1775, Asbury received a letter from the man with whom he had shared leadership for a time, Thomas Rankin, saying the decision had been made that all English Methodist missionaries were to return to England because of the growing unrest. Asbury’s response was firm:

I can by no means agree to leave such a field for gathering souls to Christ, as we have in America. It would be an eternal dishonour to the Methodists, that we should all leave 3,000 souls, who desire to commit themselves to our care; neither is it the part of a good shepherd to leave his flock in time of danger: therefore, I am determined, by the grace of God, not to leave them, let the consequence be what it may. 10

Asbury continued his preaching efforts with little interference. By early spring of 1778, all the English Methodists in leadership had left except for Asbury. However, he was vehemently determined to focus on spreading the work of Christ and to ignore politics as much as possible.

Freedom Comes to America

In February 1782, the British Parliament voted not to continue the war in America. The end of the conflict brought many changes for Asbury and Methodism. The traveling restrictions were minimized, but until a treaty was officially signed, Asbury was still suspect and had to obtain a valid pass to move about. Such inconveniences were minor compared to more drastic ministry needs. While the attendance and ministry of most churches had diminished during the trials of war, Methodism had actually grown. In 1773, American Methodism had 24 preachers, 12 circuits, and 4,921 members; by the end of the war, there were 82 Methodist preachers, 39 circuits, and membership of 13,740.11

Given the growth, John Wesley seemed to feel obliged to exercise his leadership again as the father of the movement. However, when Wesley tried to regain control by sending Thomas Coke as co-superintendent with Asbury, Coke got an earful. The story goes that Coke interrupted American Methodist preacher Nelson Reed to say, “You must think you are my equal,” to which Reed responded, “Yes, Sir, we do; and we are not only the equals of Dr. Coke, but of Dr. Coke’s king.” 12 Asbury leaned on this independent, democratic spirit to solidify - once and for all - his leadership of the Methodist movement in America by calling for a vote from the combined northern and southern conferences. This was in direct opposition to John Wesley’s method of appointing leaders rather than electing them. It would prove the final break with English leadership.

On December 27, 1784, the Americans voted - and they chose Asbury to be superintendent of the newly formed Methodist Episcopal Church. Methodism was its own denomination and Asbury its bishop. By 1787, the American leadership had rejected the last of Wesley’s directions, effectively declaring American Methodism’s independence.

“Live or Die I Must Ride”

While many new leaders would have set up a base of operations in a capital city, Francis's heart led him to travel the nation as a circuit rider. This leading proved to be of great benefit: as Bishop Francis was also a travelling ordination service. Whenever he came to a new area and found a young man worthy of ministry, he ordained him on the spot and appointed him to a freshly created circuit. Each Methodist preacher was responsible for a circuit that was between two hundred and five hundred miles in circumference. He was expected to visit each preaching site every two to six weeks.

Thus, Methodism grew as a web-like network across the new territories, and with it, the Gospel became the common language of America, from the original Plymouth settlement to the farthest reaches of Kentucky and beyond. “No family was too poor, no house too filthy, no town too remote, and no people too ignorant to receive the good news that life could be better.” 13

Other denominations simply could not keep up with Asbury’s pace. College education was the primary avenue to success for mainline clergy, but Methodist preachers preferred to be without credentials so that they could better relate to the common people. Asbury certainly didn’t discourage learning, but he didn’t want anything to distract a man from speaking “the plain truth to plain people.” 14 Only four questions were posed to evaluate prospective Methodist itinerant preachers: “1) Is this man truly converted? 2) Does he know and keep our rules? 3) Can he preach acceptably? 4) Has he a horse?” 15

Dinner with President Washington

Slavery was a troubling subject for Asbury and for the Methodist organization in general. Asbury could not understand how a country that fought so passionately for freedom could make slaves of other human beings. He made sure that the slaves felt welcomed by every preacher and were always included with their masters in Methodist Episcopal services. Asbury drew no colour line for ministers either. He did not hesitate to travel with Harry Hosier, the first African-American Methodist evangelist, to the state of Virginia. Many Methodists considered Hosier to be one of the best preachers in the world.

After the Revolutionary War, Francis and Thomas Coke made an attempt to get President George Washington to sign a petition to emancipate the slaves. Visiting him at Mount Vernon, Asbury felt uncomfortable having black servants wait on them at dinner. Afterwards, Washington said that although he agreed with the principle, he would not sign the petition. He explained that the slaves needed to be educated so that they would understand their obligation of freedom; otherwise, freedom would not be a gift. Washington himself owned several hundred slaves who worked his plantation, but a few months before he died, he changed the specifications of his will so that they would all be set free when his wife died. The degree to which Asbury may have influenced that decision is uncertain.

The Holy Spirit Explosion on the Western Frontier

In June 1800, James McGready, the pastor of three small congregations at Red River, Gaspar River, and Muddy River, invited the local ministers to join him at the annual Communion gathering at the Red River Church. The event would take place over a weekend with Communion to be served on Monday. The initial days were quiet, but when one of the local preachers spoke on Monday morning, the Spirit of God fell on a woman and she began shouting and singing. Presbyterian minister John McGee, who was sitting in the congregation as the minister brought his message to a close, began weeping. It was not long before the rest of the congregation was weeping as well, crying out for salvation.

Then, McGee spoke and exhorted the crowd to let “the Lord God Omnipotent reign in your hearts, and to submit to Him.” He later recalled, “I turned to go back and was near falling; the power of God was so strong upon me. I turned again and, losing sight of the fear of man, I went through the house shouting and exhorting with all possible ecstasy and energy, and the floor was soon covered with the slain.” 16 The power of God fell and people dropped to the ground everywhere.

In the following months, similar meetings were organized. The summer of 1801 was a literal Pentecost season with spiritual manifestations that would sweep holding camp meetings into popularity for many decades to come. The revival reached its height at the Cane Ridge camp meeting that August.

It didn’t take long for many mainline ministers to condemn this emotionalism, as their predecessors had during the Great Awakening. Asbury, however, saw the work of God rather than excess, so he embraced the camp meeting movement to the point that he urged Methodists in the East to imitate this format in their own districts hoping for the same movement of God to revive souls. These people needed to be shepherded, and if the Presbyterians and the Baptists weren’t going to do it, then the Methodists certainly would.

“What Shall I Do When I Am Old?”

By 1813, when Francis was sixty-eight, his body began giving out from all of the years in the saddle. Added to this, he had rheumatoid arthritis; and has he grew older, the ailment was so severe that he gave up horseback riding and had to be transported by carriage.

In 1816 he and a travelling companion were on their way to Fredericksburg, pushing hard in hopes of making it to the General Conference. When Francis could go no farther, they took shelter at the home of an old friend, George Arnold. The next morning was the Sabbath, and he asked that the family gather around him for worship. His lungs had filled with fluid, so he had to be propped up in a chair. At the end of the singing and preaching by his travelling partner, Asbury did as he always did - he called for the plate to be passed so a collection could be taken for the needs of his fellow preachers. In a final act of praise, he raised his hands in triumph when asked if he felt the Lord Jesus was precious. Francis Asbury passed away at four o’clock that afternoon, on Sunday, March 31, 1816.

Works Consulted

- The exact date of Francis Asbury’s birth is actually uncertain. Sources state that it could have been a day earlier (August 19) or later (August 21).

- John H. Wigger, “Holy, ‘Knock-’em-down’ Preachers,” Christian History 14, No. 1 [Issue 45] (1995): 25.

- Asbury, The Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury, vol. I, 722, in Darius L. Salter, America’s Bishop: The Life of Francis Asbury (Nappanee, IN: Francis Asbury Press, 2003), 28.

- Salter, America’s Bishop, 36.

- Asbury, The Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury, vol. I, 4, in Salter, America’s Bishop, 36.

- Ezra Squier Tipple, Francis Asbury: The Prophet of the Long Road (New York: The Methodist Book Concern, 1916),111–112.

- Salter, America’s Bishop, 38.

- Tipple, Francis Asbury: Prophet of the Long Road, 120.

- Asbury, The Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury, vol. I, 294, in Salter, America’s Bishop, 71. Emphasis added.

- Asbury, The Journal and Letters of Francis Asbury, vol. I, 161, in Salter, 55-56.

- Minutes of the Annual Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, 1773–1828 (New York: Mason and Lane, 1840), 7, 17–18, in L. C. Rudolph, Francis Asbury (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1966), 42.

- John Vickers, Thomas Coke: Apostle of Methodism (New York: Abingdon Press, 1969), 119, in Salter, 87.

- Salter, America’s Bishop, 167.

- “A Grassroots Movement,” The Methodist Church website, http://www.methodist.org.uk/index.cfm?fuseaction=opentogod.content&cmid=1498.

- Timothy K. Beougher, “Did You Know?” Christian History 14, no. 1 [Issue 45] (1995): 3.

- Mark Galli, “Revival at Cane Ridge,” Christian History 14, no. 1 [Issue 45] (1995): 11.

Receive a periodical newsletter about this Author. Links in connection with Articles related to this Author will be periodically sent to your email.

Related Topics : Generals Of God, Roberts Liardon, Francis Asbury,

At IUSEFAITH.com and JUTILISELAFOI.COM, we are dedicated to curating and delivering powerful devotionals from genuine, Spirit-led men and women of God. Through reading, analysis, translation, programming, and occasionally content generation, we ensure you receive rich, faith-building resources.

To continue expanding this work and reaching more souls, we are upgrading to a higher hosting plan. If you are led to support this Kingdom mission, kindly reach out via +233 552 524 195 to learn how you can contribute.

Together, let’s advance the Gospel through technology.