with voice

commands, please use

the Chrome browser on PC

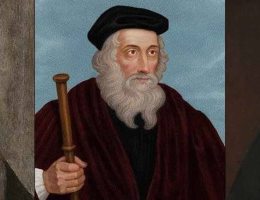

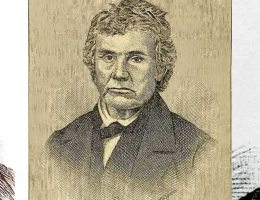

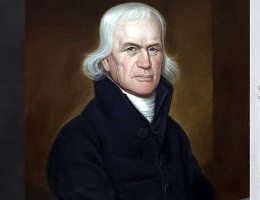

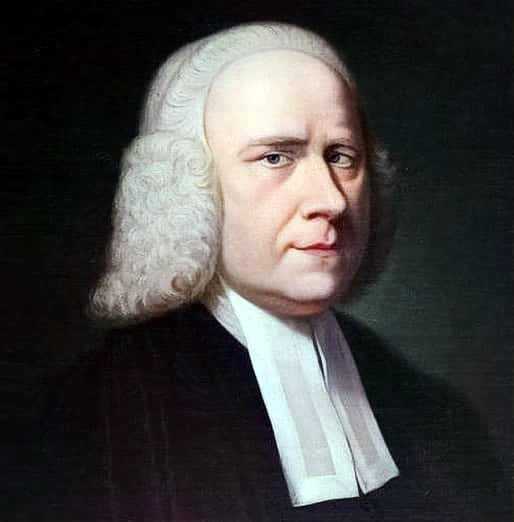

George Whitefield

Date of Birth : December 16, 1714.

Fell As Sleep in The Lord : September 20, 1770.

Marriage : November 14, 1741.

Children : 1, but he died in infancyGod forbid that I should travel with anybody a quarter of an hour without speaking of Christ to them.

George Whitefield - known as the “Great Orator,” the “Divine Dramatist,” and the “Heavenly Comet” for his style and impact on all who heard him - was an evangelistic pioneer. Moved with such deep compassion for the lost, he was the first in the Great Awakening to preach “out in the open” to coal miners and shipyard workers as they passed on their way to and from work, for they had no other opportunities to hear the Gospel. His charisma and compassion carried him from parlours to prisons in England and from politicians’ houses to Native Americans’ huts in the New World.

George Whitefield - known as the “Great Orator,” the “Divine Dramatist,” and the “Heavenly Comet” for his style and impact on all who heard him - was an evangelistic pioneer. Moved with such deep compassion for the lost, he was the first in the Great Awakening to preach “out in the open” to coal miners and shipyard workers as they passed on their way to and from work, for they had no other opportunities to hear the Gospel. His charisma and compassion carried him from parlours to prisons in England and from politicians’ houses to Native Americans’ huts in the New World.

George Whitefield was born to innkeepers in the cosmopolitan city of Gloucester, England. He was the youngest of seven children. Two years after George’s birth, his father passed away and his mother was left alone to run the inn and care for the family.

When George was ten years old, he attended grammar school at St. Mary de Crypt where he discovered a love of theatre. Although he progressed rapidly in the standard classical studies, his passion for winning the lead role in school plays was all-consuming. Because of his acclaimed oratory abilities, he was also called upon to deliver a speech whenever important people visited the school.

The Dawn of Destiny Breaks Forth

George Whitefield was eighteen when he entered Pembroke in November 1732. Because his family was poor, George worked to earn his way through college as a servitor to wealthier students. Sometime in 1735, Whitefield learned that a woman in one of the workhouses had attempted to cut her own throat. Knowing that John and Charles Wesley would be willing to counsel her, he sent them word via an apple seller who divulged her source to Charles even though George had charged her not to. Charles sought George out and invited him to breakfast.

Charles, a college tutor and six years George’s senior, was impressed by Whitefield and invited him to join the Holy Club. Their friendship flourished rapidly. Charles lent him several life-transforming books, of which the most profound was the Life of God in the Soul of Man by Henry Scougal. After reading this book, Whitefield wrote that through it,

Jesus Christ first revealed Himself to me and gave me the new birth. I learned that a man may go to church, say his prayers, receive the Sacrament, and yet not be a Christian. How did my heart rise and shudder like a poor man that is afraid to look into his ledger lest he should find himself bankrupt?

He wasted no time delving deeper into the Gospel while the Wesleys were still “stumbling in the mazes of salvation by conduct.” It would take the Wesley brothers three more years to experience the magnitude of God’s saving grace and receive the new birth themselves.

The Boy Preacher

Whitefield delivered his first sermon as a deacon from the pulpit of St. Mary de Crypt in Gloucester, not far from where he had served as a common tapster not five years earlier. Probably out of curiosity more than anything else, a surprisingly large crowd gathered to hear him preach a message entitled “The Necessity and Benefit of Religious Society.” As a result of this message, fifteen people were reported to have “gone mad” from an overwhelming conviction of their sins. The bishop responded that he hoped “the madness might not be forgotten before next Sunday."3"

From the beginning, Whitefield’s preaching reflected years of theatrical performances and a heart filled with intense devotion. The pulpit was his stage, and he would use every ounce of intellect and talent to convey his sermon points. A famous actor of the time, David Garrick, exclaimed, “I would give a hundred guineas if I could say ‘Oh’ like Mr Whitefield.” 4

America Calling

George soon received a letter from John Wesley imploring him to come to America “where the harvest is so great and the labourers so few. What if thou art the man, Mr Whitefield?” “Upon hearing this,” wrote Whitefield, “my heart leapt within me, and, as it were, echoed to the call!”5

Roughly a year later, George set sail for America. As Whitefield’s ship, the Whitaker, was heading for the open sea, John Wesley was just returning to England, having determined Georgia a failure. The two ships had, in fact, passed within sight of each other along the English shoreline, though neither at the time knew a friend was aboard the other.

The Whitaker arrived in Georgia on May 7, 1738. From the outset, Whitefield was moved by the living conditions of the poor, and especially by the growing number of orphans. One month after his arrival, he began to teach the children in the surrounding villages and made arrangements to establish a school in Savannah. He also felt compelled to begin plans for an orphanage that would eventually be named Bethesda. He soon decided he would have to return to England to secure funding for the care of widows and orphans in the colonies. He also needed to complete his ordination as a priest.

All the Trees of the Field Shall Clap Their Hands

When Whitefield returned to London in December 1738, he found much had changed. Foremost, Charles and John Wesley had experienced their own personal conversions through the work of the Moravians and were preaching at Oxford and elsewhere on the “new birth.” Their message, combined with the strictness of their moral code, had incurred waves of opposition in the city. Due to Whitefield’s association with the “Methodists,” pulpits had become less welcoming to him as well.

In spite of this, Whitefield was ordained into the Anglican priesthood on January 14, 1739. He managed to preach to large crowds at the few remaining churches that would admit him, collecting significant financial contributions for the orphanage he proposed in Savannah. His celebrity, as well as his charity, caught the interest of the Countess of Huntingdon, who invited him to deliver a presentation to a gathering of her aristocratic friends. She and several of her peers were soon counted among his most faithful supporters and patrons.

Open-Air Preaching

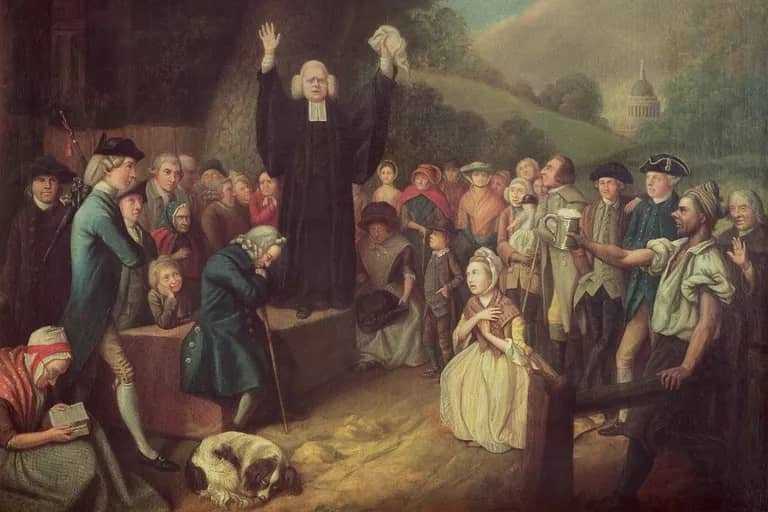

From London, Whitefield made his way to Bristol, where he found the religious atmosphere cold and unwelcoming. Being censored by the established churches, he went to the mining district of Kingswood - where there was no church - to preach to the coal miners. He recorded his first experience preaching out in the open, saying in part:

From London, Whitefield made his way to Bristol, where he found the religious atmosphere cold and unwelcoming. Being censored by the established churches, he went to the mining district of Kingswood - where there was no church - to preach to the coal miners. He recorded his first experience preaching out in the open, saying in part:

I went upon a Mount, and spake to as many people as came unto me. They were upwards of two hundred. Blessed be to God, I have now broken the ice; I believe I never was more acceptable to my Master than when I was standing to teach those hearers in the open fields.6

Whitefield went on to write that he could see the “white gutters made by their tears, which plentifully fell down their black cheeks.” 7 The more he took to field preaching, the more he received hostility from the churches.

After a brief stint back in London, Whitefield returned to Bristol with Charles and John Wesley near the end of March 1739. There, in the town centre, he stepped up on a low wall and began to exhort the townspeople as they passed by. George’s example soon had Wesley’s preaching in the open-air themselves, satisfied that they would do so for the rest of their lives. George left the Wesleys in the provinces and returned to London where revival sprang up wherever he preached. The Great Awakening was now in full swing.

Awakening America

On October 30, 1739, Whitefield returned to America and travelled immediately to Philadelphia. It was not long before even the largest of churches proved too small to hold the throngs of people pushing their way in to hear Whitefield. From Philadelphia to New York, he spoke to record-sized audiences - those who gathered to hear him often outnumbered the population of the local towns and cities!

Benjamin Franklin heard Whitefield preach when he first arrived in Philadelphia, and wrote, “He had a loud and clear voice, and articulated his words and sentences so perfectly, that he might be heard and understood at a great distance, especially as his auditories, however numerous, observed the most exact silence." 8

Franklin and Whitefield would share a lifelong friendship. From the outset, Franklin offered to publish Whitefield’s sermons in his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, and later his journals. Franklin would even help Whitefield raise money for the orphan house. He was so taken with Whitefield’s fundraising ability that he wrote:

I happened soon after to attend one of his sermons, in the course of which I perceived he intended to finish with a collection, and I silently resolved he should get nothing from me. I had in my pocket a handful of copper money, three or four silver dollars, and five pistols in gold. As he proceeded I began to soften and concluded to give the coppers. Another stroke of his oratory made me ashamed of that and determined me to give the silver, and he finished so admirably, that I emptied my pocket wholly into the collector’s dish, gold and all 9

Adding Fuel to the Fire

By mid-October 1740, Whitefield found himself in Northampton, Massachusetts, the guest of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards. Jonathan was so moved by Whitefield’s sermons that he was known to break down in tears as he listened. Sarah was also taken with Whitefield’s oratorical abilities, and wrote,

It is wonderful to see what a spell he casts over an audience by proclaiming the simple truths of the Bible. I have seen upwards of a thousand people hung on his words with breathless silence, broken only by an occasional half-suppressed sob. . . . A prejudiced person, I know, might say that this is all theatrical artifice and display; but not so will anyone think who has seen and known him 10

Whitefield’s presence in Northampton had the effect of fresh fuel applied to an already kindled fire. While Edwards preached fear of God’s judgment, Whitefield preached God’s mercy and acceptance. He recorded, “I found my heart drawn out to talk of scarce anything else besides the consolations and privileges of the saints and the plentiful effusion of the Spirit upon believers.” 11 Hearts that had already been “scorched and broken with the fires of judgment” 12 melted at the sound of Whitefield’s compassionate words.

Division with the Wesleys

Beginning in 1741, divisive public debates that lasted nearly a year created two camps among the Methodists: the Wesleys’ “free grace” societies and Whitefield’s Calvinists. Soon both Whitefield and the Wesleys saw the danger of the split - they realized the opposition they felt toward one another was scarcely as strong as the opposition between their followers. Though they could not reconcile their organizations, not one of the three could bear to be separated “in spirit” from the others for long. Their friendships would be rejoined, but the two movements of Whitefield’s “Calvinistic Methodism” and the Wesleys’ “United Societies” would not.

The Cambuslang Communion

Having conquered England and North America, Whitefield shifted his aim to awaken Scotland. Calvinists all, Americans and Scots were kindred spirits in the eighteenth century, and Whitefield found great success among both. Whitefield would visit Scotland fourteen times, experiencing a depth of revival he had not witnessed in the rest of Great Britain or the colonies. He reminisced later in life about the joy he always found in speaking to the Scots; he was “impressed by the ‘rustling made by opening the Bibles’ as soon as he ‘named’ his text.” 13

He put a small town named Cambuslang, just southeast of Glasgow, on the map after he preached to twenty thousand twice in one day and to thirty thousand the next. He had never witnessed such a hunger for the presence of God. Enormous tents were set up to accommodate the thousands desiring to partake in Communion, while worship and prayer continued into the early hours of morning. He recorded:

You might have seen thousands bathed in tears. Some at the same time wringing their hands, others almost swooning, and others crying out, and mourning over a pierced Saviour. . . . All night in different companies, you might have heard persons praying to and praising God. . . . It was like the Passover in Josiah’s time. 14

This scene would repeat itself wherever Whitefield ventured to preach; it is said that the fires kindled during these “Cambuslang Revivals” set all of England aflame.

George Marries

Near the end of 1741, Elizabeth Burnell James, a widow, agreed to marry Whitefield even though he made it clear that preaching the Gospel would always be his first love. Elizabeth was thirty-six and Whitefield twenty-six. During their weeklong honeymoon, Whitefield preached twice a day. Within the month, he was back on the road; thereafter, he would rarely see, or even speak of, his new wife. Elizabeth set up residence in London; George would only stay there for short periods as the call of evangelism tugged constantly at his heart.

In 1744, Elizabeth gave birth to a son who died in infancy. This loss weighed heavily on George, and from that point, he showed special concern for children everywhere. He was known to speak directly to them when he preached, telling them that if their parents would not come to Christ, they were to come anyway and go to heaven without them. After the loss of their son, Elizabeth went on to suffer four miscarriages. Although observers noted that George was always respectful and courteous towards his wife, Elizabeth wrote of her marriage, “I have been nothing but a load and burden to him.” 15

Persecution and Triumph

The years following 1741 were filled with incredible evangelistic victories - as well as with the most violent persecution. George was frequently pelted with stones, rotten vegetables, and dead animal parts as he spoke. On one occasion, a rock struck his head and nearly rendered him unconscious. On another occasion, he would have been stabbed had the crowd not intervened on his behalf. Another time, a man tried to strike him with a whip as he preached; on other occasions, protestors attempted to drown out his voice with drums or trumpets. In 1744, an intruder broke into his home and attacked him in his bed. His life was preserved thanks to his landlady who - when Whitefield screamed, “Murder!” - came running and shouting, waking the entire neighborhood and sending the assailant fleeing into the night.

Following a third successful trip to America in 1745, George returned again to England, Scotland, and Wales. He earned further attention and respect from the wealthy Lady Huntingdon. She appointed him chaplain of a network of chapels she had built, a position that relieved some of his financial burdens. The demand for his preaching did not slacken; persecution did, fortunately. During the 1750s, both camps of the Methodists had gained popular support as their message became more widely accepted among all ranks of society. As individuals, they had also mellowed. Whitefield learned to use a gentler tone in his letters and public declarations, ruffling far fewer feathers as he grew older.

In August 1768, after twenty-seven years of marriage, Elizabeth entered heaven’s gates two years ahead of her husband. After she died, George said, “I feel the loss of my right hand daily.” 16

The Final Visit to America

Almost exactly one year later, Whitefield returned to the colonies in November 1769. Although he was not in good health when he arrived in Charleston, he preached to large crowds for ten consecutive days. He continued his preaching tour throughout New England as if he were still a youthful man. He insisted to his friends that he “would rather wear out than rust out.” 17

On the morning of September 19, 1770, he preached a moving message in Portsmouth, New Hampshire and then set out immediately for his next destination: Newburyport, Massachusetts. Friends and admirers observed his weakened condition and begged him to rest, but he pressed on. By midday, Whitefield was implored by a gathering crowd to preach, and he complied. He climbed atop a barrel in an open field to preach what would be his last sermon. The text he spoke about was “Examine yourselves whether ye be in faith,” which discussed the new birth. Whitefield’s last public words were about the uselessness of works to get to heaven: “Works! Works! A man gets to heaven by works! I would as soon think of climbing to the moon on a rope of sand.” 18George Whitefield breathed his last in the early hours of September 20, 1770, the very next day. He was fifty-six years old.

Works Consulted

- From a sermon given by Whitefield in 1769, quoted in Henry Scougal, The Life of God in the Soul of Man (London: InterVarsity Fellowship, 1961), 12.

- Albert D. Belden, George Whitefield - The Awakener: A Modern Study of the Evangelical Revival (Nashville, TN: Cokesbury Press, 1930),19.

- Stuart Clark Henry, George Whitefield: Wayfaring Witness (New York: Abingdon Press, 1957), 28.

- Harry S. Stout, “Heavenly Comet,” Christian History 12, no. 2 [Issue 38] (1993): 10.

- Belden, George Whitefield - The Awakener, 31.

- Stuart Clark Henry, George Whitefield: Wayfaring Witness (New York: Abingdon Press, 1957), 48.

- John Gillies, Memoirs of Reverend George Whitefield (New Haven: Whitmore & Buckingham, and H. Mansfield, 1834), 39.

- Benjamin Franklin, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, http://www.kellscraft.com/FranklinAutobio/FranklinAutobiographyCh11.html.

- Ibid.

- Stout, “Heavenly Comet,” 13.

- Belden, George Whitefield - The Awakener, 113.

- Ibid.

- Henry, George Whitefield - Wayfaring Witness, 79.

- Ibid., 78.

- Mark Galli, “Whitefield’s Curious Love Life,” Christian History 12, no. 2 [Issue 38] (1993): 33.

- Galli, “Whitefield’s Curious Love Life,” 33.

- Stout, “Heavenly Comet,” 14.

- Ibid., 15.

Receive a periodical newsletter about this Author. Links in connection with Articles related to this Author will be periodically sent to your email.

Related Topics : Generals Of God, Roberts Liardon, George Whitefield,

At IUSEFAITH.com and JUTILISELAFOI.COM, we are dedicated to curating and delivering powerful devotionals from genuine, Spirit-led men and women of God. Through reading, analysis, translation, programming, and occasionally content generation, we ensure you receive rich, faith-building resources.

To continue expanding this work and reaching more souls, we are upgrading to a higher hosting plan. If you are led to support this Kingdom mission, kindly reach out via +233 552 524 195 to learn how you can contribute.

Together, let’s advance the Gospel through technology.