with voice

commands, please use

the Chrome browser on PC

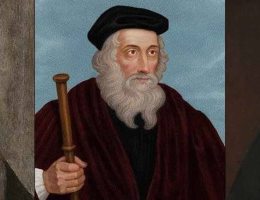

Date of Birth : June 17, 1703.

Fell As Sleep in The Lord : March 2, 1791.

Marriage : Oct. 18, 1751.

Children : NoneI look upon all the world as my parish; thus far I mean, that, in whatever part of it I am, I judge it meet, right, and my bounden duty to declare unto all that are willing to hear, the glad tidings of salvation.

During his ministry, John Wesley rode over 250,000 miles by horseback to preach the Gospel - a distance comparable to circling the globe ten times. He preached more than forty thousand sermons and published more than five thousand sermons, pamphlets, and books of all kinds. John brought the challenge of new life to the English church when it had lost sight of Christ as the ultimate Redeemer. John Wesley's - with his brother, Charles' - passionate efforts were felt not only in England but also throughout continental Europe and the developing world - predominantly in America. Methodism would pave the way for revival far into the century following his death.

John Benjamin Wesley, known to his family as “Little Jackie,” was born in the Epworth parsonage of his parents, Rev. Samuel and Susanna Wesley. John was the fifteenth of nineteen children. His brother Charles, who would later be his partner in establishing the Methodist movement, was the eighteenth and born just four years later on December 18, 1707. Of the nineteen children, only ten would live into adulthood.

The Wesley home was governed by strict moral principles, exercised daily through rigorous discipline in manners, study, and prayer. Their mother, Susanna, saw that all of the children were trained in academics and etiquette from birth. From one year of age, they learned to fear the rod and to cry softly and sparingly. As a result, although the house was full of children, it was always peaceful and quiet. It was a discipled lifestyle that would later show up in John's pursuit of God.

Trial by Fire

As the Wesley household slept the night of February 9, 1709, the Epworth parsonage was mysteriously set ablaze sometime between eleven and twelve o’clock. John’s sister, Hetty, alerted the family to the fire when part of the thatch roof fell on her bed. There was no time to grab either clothes or possessions. Susanna was near term with her last child and suffered some burns as she lingered trying to ensure everyone got out safely. Once outside everyone was accounted for except five-and-a-half-year-old Jackie. While Susanna searched outside, Samuel made two attempts to reenter the house, but the fire was too much. Failing, he gathered his family around him in the garden to pray, commending his son to God.

As the Wesley household slept the night of February 9, 1709, the Epworth parsonage was mysteriously set ablaze sometime between eleven and twelve o’clock. John’s sister, Hetty, alerted the family to the fire when part of the thatch roof fell on her bed. There was no time to grab either clothes or possessions. Susanna was near term with her last child and suffered some burns as she lingered trying to ensure everyone got out safely. Once outside everyone was accounted for except five-and-a-half-year-old Jackie. While Susanna searched outside, Samuel made two attempts to reenter the house, but the fire was too much. Failing, he gathered his family around him in the garden to pray, commending his son to God.

About that time, John caught the eye of a neighbour as he waved frantically from a second-story window. Climbing atop another man’s shoulders, he pulled John to safety. In the next few minutes, the entire rectory burned to the ground. Afterwards, John’s father famously remarked, “Is not this [John] a brand plucked out of the burning?” From that point on, Susanna was convinced that John had a special call of God on his life.

The “Holy Club”

At the age of seventeen, John went on to Christ Church, Oxford. He was a small man physically - only five feet five and a half inches tall, weighing roughly 130 pounds - but soon grew to tower over his peers spiritually.

Near the end of his studies, John met a porter (luggage carrier) who owned only one coat and had consumed nothing but a drink of water that entire day, yet his heart overflowed with praise to God. John remarked, “You thank God when you have nothing to wear, nothing to eat, and no bed to lie upon. What else do you thank Him for?” The man answered, “I thank Him, that He has given me my life and being, a heart to love Him, and a desire to serve Him.” John realized there was something more to following Jesus than he had yet to experience personally - and it was something he wanted.

Thus John began a “methodical” search for God. He set himself to a disciplined routine of prayer, Bible study, church attendance, fasting, and good works in hope of finding it.

It was about this time, in 1729, that Charles Wesley started to meet with several spiritually-minded students to study, pray, and observe daily disciplines together. John accepted an invitation to join them and was soon serving as their mentor. The group was mockingly called the “Bible Moths,” “Bible Bigots,” “Sacramentarians,” “Methodists,” the “Holy Club,” or “Enthusiasts.” However, over the next few years, the group proved to be a force for good that could not be ignored as they visited prisoners and ministered to orphans and the destitute. They soon numbered about twenty-five, among whom was George Whitefield.

Georgia

Shortly after John and Charles’ father’s death in 1735, Colonel (later General) James Oglethorpe, a former friend of their father, suggested John accompany him as chaplain to the new settlement in Savannah, Georgia. John accepted and asked Charles to join him. Oglethorpe appointed Charles as his secretary. The brothers and two other Holy Clubbers, Benjamin Ingham and Charles Delamotte set out for America aboard the Simmonds on October 21, 1735. Charles was ordained on the eve of the voyage.

The journey to America proved to be a succession of storms. Faced with death at the hands of these tempests, John found himself surprisingly unprepared to face his Maker. In contrast to this, there was a group of German Moravian missionaries onboard who showed no such fear. In fact, in the midst of one of the storms, they were holding a service and singing a psalm when a wave crashed over the vessel, shredded the mainsail, flooded the decks, and poured into the levels below with such force that many thought the ship was lost. As others screamed in terror, the Moravians sang on without interruption. Never had John met one person - let alone an entire group of men, women, and children - so unafraid of death.

The Simmonds landed in Georgia on the morning of February 5, 1736. Savannah was a settlement of fewer than two hundred buildings with a population of only about 520. In his first few weeks, John made contact with the Native Americans who received him heartily. It gave him great hope for what he would accomplish.

A Mismanaged Romance

John’s stay would be significantly shortened when his heart fell for the chief magistrate's daughter, Sophia “Sophie” Christiana Hopkey. Over the first year, they grew close, but when colleague Charles Delamotte questioned John about the relationship, his resolve to marry her wavered. John decided to go to the board of Moravian elders for guidance. Bishop David Nitschman, who John had approached in private about the matter shortly before this, asked if John was willing to abide by their advice. John hesitantly agreed. “Then,” replied Nitschman, “we advise you to proceed no further in this business.” In his journal, John likened this to God commanding him “to pull out my right eye; and by his grace, I determined to do so.”

John could not bring himself to confront Sophie with his decision and treated her coldly in the coming days. In response, Sophie married a reputable young man named Williamson on March 12, 1737, only four days after they were engaged.

Several weeks later, John refused to serve Sophia and her husband Holy Communion, stating he knew them to be out of fellowship with God. Williamson took this prohibition personally and sued John for defamation of character. For a number of reasons, the trial was delayed for months in which time John’s ministry grew increasingly ineffective and his financial support dried up. After much deliberation and prayer, he decided to return to England and set sail aboard the Samuel on December 22, 1737.

A “Heart Strangely Warmed”

Only four days after returning to London, John met a Moravian missionary named Peter Bohler who had just recently been ordained. John and Peter began a religious dialogue that continued over the next several months.

During this time, Charles became sick with pleurisy and was cared for in the house of a man named Bray, a “poor ignorant mechanic . . . who knew nothing but Christ.” While there, on May 21, 1738, Charles found that the “assurance of his salvation” Bohler had been teaching the brothers about was indeed possible. In that same hour, Charles’ strength returned, and he rose up, healed.

John was pleased for his brother, but he could not help feeling even less worthy of salvation than he had before. Then, a few evenings later on Wednesday, May 24, John found this assurance for himself:

In the evening I went very unwillingly to a [Moravian] society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther’s preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change in which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone, for salvation; and an assurance was given me that He had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.

The Great Awakening

On New Year’s Day, 1739, the Wesley brothers hosted a love feast to celebrate the coming of the New Year with about sixty others, including George Whitefield and fellow missionary to Georgia, Benjamin Ingham. When the midnight hour struck, they prayed and worshipped. This continued on into the morning until, at approximately three o’clock, everyone present fell to the ground, overpowered and crying with joy. They “broke out with one voice, ‘We praise thee O God, we acknowledge thee to be the Lord.” Whitefield described this time in his journal:

It was a Pentecost season indeed: sometimes whole nights were spent in prayer. Often have we been filled as with new wine; and often have I seen them overwhelmed with the Divine Presence, and cry out, “Will God indeed dwell with men upon the earth? How dreadful is this place? This is no other than the house of God and the gate of heaven!”

That spring, upon the urging of Whitefield, John decided to take his preaching outside the church doors. His message that salvation was free to all offended many in the Calvinistic Church of England, so few would let him preach it from their pulpits. On March 30, following Whitefield’s example, John stood on a little hill outside of Bristol and delivered his first open-air message to a reported three thousand people. In the words of biographer Basil Miller, “Here was a crowd of people to whom his message came as a bursting light from heaven, and he would not deny them this glimpse of Christ.”

As he spoke in the coming weeks, the Holy Spirit began to move among the crowds. People would cry out, shout for joy, and fall down under the power of God. A witness wrote:

Blasphemers cried for mercy; sinners were smitten to the earth in deep conviction; even passing travellers were so affected. A physician studied a case of a woman whom he had known for years, and as he saw perspiration break from her face and her body shake he decided this was no mere physical disorder but that it was evidence of God’s workings.

Such scenes were frequent in society halls, barns, and the open-air alike. John would speak three or four times a day and travel as much as twenty miles by horseback to deliver the Gospel. As he preached, people would cry out as if they were about to die, prayer would be offered for them, and they would rise up, rejoicing in God their Savior. The Methodist Revival - that would go on to be known as the Great Awakening - had begun.

The Move of God Divided

While England was getting swept up in the Methodist Revival fire, problems began brewing in London. A Moravian minister named Philip Henry Molther arrived in October 1739 and began teaching that salvation was through faith alone and that there were no degrees of faith - either you had the assurance of God’s peace in your heart, or you did not. The Wesley brothers espoused that faith grew through prayer, fasting, studying the Word of God, and doing good works. The Moravians soon began to distance themselves from the Wesleys as they strained on this gnat of doctrinal difference.

About the same time, a rift between the Wesleys and Whitefield also grew concerning Calvinistic Predestination. Under the influence of American Puritan writings, George sent letters to John questioning his stand for salvation by an act of human “free will” (called “Arminianism” after one of its proponents, Dutch theologian Jacob Arminius [1560–1609]). John held strong against Whitefield’s Calvinist argument that individuals had little to do in determining their own salvation and a new division grew. By the dawn of 1741, the Great Awakening that the Moravians had seeded and the Wesleys and Whitefield had watered and brought to fruit was now three separate movements: the Wesleyan “United Societies,” Whitefield’s “Calvinistic Methodism,” and Moravianism.

Though the Wesley and Whitefield camps never rejoined, by 1742 the fierce animosity between the longtime friends—George Whitefield and the Wesley brothers—had already cooled. So, as late as 1749, the three were again ministering at the same conferences.

Marrying the Wrong Woman

On April 8, 1749, John officiated at the wedding of Charles to Sarah Gwynne. Charles and Sarah would have eight children, but only the youngest three reached adulthood: Charles Jr. (1757–1834), Sarah (1759–1828), and Samuel (1766–1837). Each grew to become an accomplished musician.

It appears that Charles’s marriage inspired John to finally put the heartache of Sophia Hopkey behind him. The previous August, he had fallen ill in Newcastle and was nursed back to health by a beautiful young widow named Grace Murray. John determined to make her his wife, but unbeknownst to him, so did another minister she had nursed named John Bennet. For months both Johns pursued Grace for her hand in marriage. Finally, she agreed to marry Wesley.

When John went to his brother for his blessings, Charles withheld his consent, feeling Grace was far from John’s social equal. John replied that Grace’s character, piety, and worth far outweighed any shame her lowly birth might cause and determined to marry Grace anyway.

However, on the way to Newcastle for a conference, Charles intercepted Grace at Hindley Hill. He kissed her on the cheek and said, “Grace Murray, you have broken my heart.” They continued on together to Newcastle, where they found Bennet. Grace fell at Bennet’s feet begging his forgiveness for playing him against John, and Bennet and Grace married less than a week later on October 3, 1749. The brothers had a tremendous falling out over this, but would not be separated for long. Oddly enough, it was George Whitefield who reunited them.

A year or so later, John slipped on a patch of ice on London Bridge and struck his ankle against the stone side so hard he couldn’t walk. He was taken to the home of a widow named Mary “Molly” Vazeille to recuperate. He remained there a week, and to everyone’s surprise, at the end of that time, on Tuesday, October 18, 1751, John and Molly married.

A year or so later, John slipped on a patch of ice on London Bridge and struck his ankle against the stone side so hard he couldn’t walk. He was taken to the home of a widow named Mary “Molly” Vazeille to recuperate. He remained there a week, and to everyone’s surprise, at the end of that time, on Tuesday, October 18, 1751, John and Molly married.

Where John’s hesitancy with both Sophia Hopkey and Grace Murray had cost him a bride, his hasty marriage to Molly would cost him a great deal more. The honeymoon was brief. Within two weeks, just enough time to have recovered sufficiently from his injury, John was on the road again. Though she had agreed to let him travel as he felt necessary, Molly was not comfortable with being left alone so much and soon grew jealous and bitter. She began reading through his personal papers and correspondence, berating him upon his return for any references to other women. Once, she locked Charles and John in a room in order to confront them with their faults, and they only escaped by quoting Latin poetry to her until she could stand no more. Another time, one of John’s staff members found Molly standing over John, clutching a tuft of his hair by which she had been dragging him around their hotel room. Molly left John several times but always returned in response to his entreaties. The marriage lasted thirty gruelling years until Molly died in 1781.

The Wesleys’ Influence Remained Until the Very End

On October 7, 1790, John Wesley preached his last outdoor sermon under an ash tree in the churchyard of Rye in Kent, crying, like “the voice of the Woes, ‘Repent!’” On February 22, 1791, he preached his last sermon from a pulpit at City Road Chapel in London. The next day, he preached for the last time this side of heaven at a friend's house in Leatherhead a sermon entitled “Seek ye the Lord while He may be found.”

By February 25, John was feeling weak, and he returned to City Road, where he slept for the next two days. On February 27, he seemed to have recovered, joining his companions for dinner. Afterwards, he retired to his room, exhausted. He did not get up again. On March 2, 1791, surrounded by loved ones, he breathed his last breath.

Works Consulted

- Robert Southey, The Life of Wesley and the Rise and Progress of Methodism (London: Frederick Warne and Company Ltd., n.d., ca. 1820), 11.

- John Telford, The Life of John Wesley (London: The Epworth Press, 1924), 31.

- Southey, The Life of Wesley, 62.

- A severe respiratory illness.

- Telford, Life of John Wesley, 100.

- John Wesley, The Journal of John Wesley, Christian Classics Ethereal Library, http://www.ccel.org/ccel/wesley/journal.vi.ii.xvi.html (accessed October 2, 2007).

- John Wesley, The Journal of John Wesley, vol. 2, ed. Nehemiah Curnock (London: Epworth Publishing, 1938), 122–125, quoted in Eddie L. Hyatt, 2000 Years of Charismatic Christianity: A 20th Century Look at Church History from a Pentecostal/Charismatic Perspective (Chicota, TX and Tulsa, OK: Hyatt International Ministries, Inc., 1996), 106.

- Southey, Life of Wesley, 122.

- Basil Miller, John Wesley: The World His Parish (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing, 1943), 71.

- Ibid., 75.

- Telford, Life of Wesley, 248.

Receive a periodical newsletter about this Author. Links in connection with Articles related to this Author will be periodically sent to your email.

Related Topics : Generals Of God, Roberts Liardon, John Wesley,

At IUSEFAITH.com and JUTILISELAFOI.COM, we are dedicated to curating and delivering powerful devotionals from genuine, Spirit-led men and women of God. Through reading, analysis, translation, programming, and occasionally content generation, we ensure you receive rich, faith-building resources.

To continue expanding this work and reaching more souls, we are upgrading to a higher hosting plan. If you are led to support this Kingdom mission, kindly reach out via +233 552 524 195 to learn how you can contribute.

Together, let’s advance the Gospel through technology.